The weekend before last, my friend Jenny and I drove to Death Valley National Park to see the super bloom, a term used to describe the millions of wildflowers that have sprung up over the park in recent weeks thanks to El Nino’s rainfall (here’s the National Park Service’s wildflower blog with the latest updates). The last time this occurred was in 2005 — over a decade ago. So we made plans to drive up on a Saturday morning and come back Sunday afternoon, just enough time to appreciate the flowers and take in a few other iconic sites at Death Valley National Park.

After stopping at Priscilla’s Coffee & Tea, we’re good to go.

I love a good road trip. Part of the fun is just getting there — the windows down, iced coffee in hand, music blasting, and the open road stretching towards the horizon.

California is remarkably large in size and huge swathes of it are uninhabited desert. I always forget this until we get about an hour outside of Los Angeles and lose cell service; we don’t get a signal again until we reach our hotel in Nevada later that night. And for about three hours the drive looks like this:

We pass through the Searles Valley. While that white stretch below might look like snow, it’s actually salt — there’s a plant to harvest minerals and the town here centers around this industry.

Train cars line up under a bright blue sky:

We drive further north and pass through another valley, one with less salt and more dry / desert-like views:

I grew up on the relatively flat east coast and the novelty of turning a corner to find a large mountain has yet to grow old. Love this view from our windshield:

One stretch of road is all gravel — it’s only about a mile or so, but it’s not pleasant for our little car.

Now we’re headed over the last mountain range — Death Valley is on the other side of these hills:

Looking back down on the road we came in on, waaaaay below:

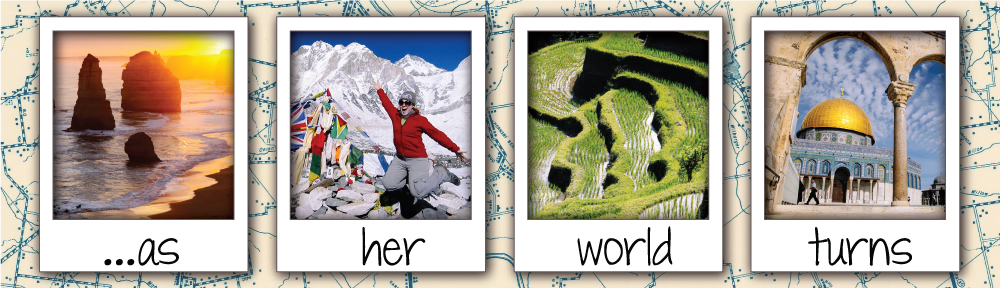

And… now we are officially in Death Valley National Park. Still have a ways to go to the first inhabited area (Stovepipe Wells) and then the main village (Furnace Creek). Here’s a map:

We stop at Stovepipe Wells to use the restroom and stretch our legs.

There’s a campground here (one of several in the park) as well as a hotel. Almost everything in Death Valley is fully booked this weekend due to interest in the super bloom.

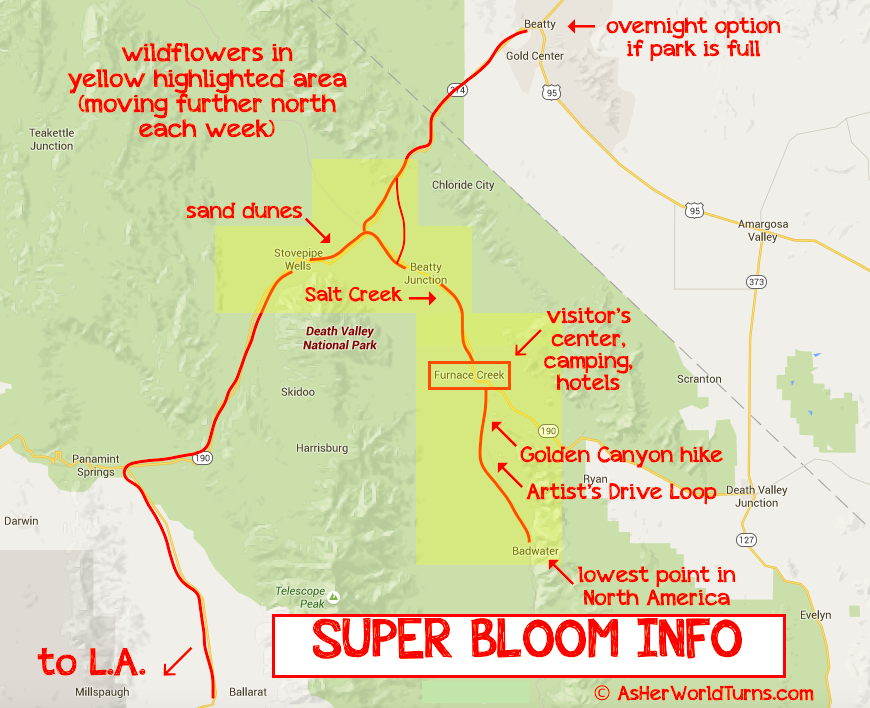

Death Valley is a very different place in the summer; temps top 120 degrees on most days in July and August. This sign below notes that for many years the hottest temperature recorded on earth was 134 degrees Fahrenheit at Death Valley back in 1913.

On average Death Valley receives just over two inches of rain per year, but last October they got 3.5 inches in just five hours. That storm wiped out some roads and shut down Scotty’s Castle, a landmark in the park. But it was enough rain to give life to millions of wildflowers and now there is a sea of yellow buds all over the valley.

We notice the abundance of flowers shortly beyond Stovepipe Wells and pull over for the first of many photo ops.

We’re not the only ones; lots of visitors are here this weekend for the super bloom. Luckily there are plenty of places to safely pull over along these roads for photos.

While most of the buds are yellow, there are some white and purple flowers too.

Again, the white in the distance below is salt, not snow. Death Valley is the lowest place in North America — 280 feet below sea level at its deepest spot — and there is a lot of salt here.

There are three conditions that make it an ideal place for salt flats:

1) There is a source of salt and minerals in these mountains.

2) There is an enclosed basin (the valley of Death Valley) that holds the concentrated salt. This area is the size of New Hampshire!

3). There is an arid climate where evaporation exceeds precipitation, which leaves behind the salt flats.

At sea level and heading lower.

That area is Salt Creek in the distance. Jenny and I will check that out shortly.

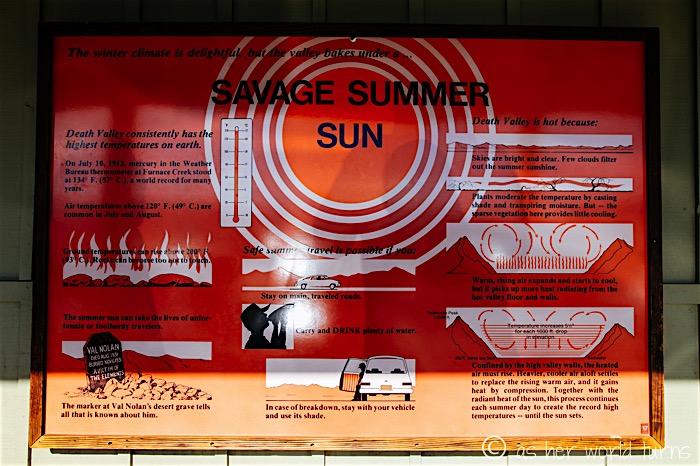

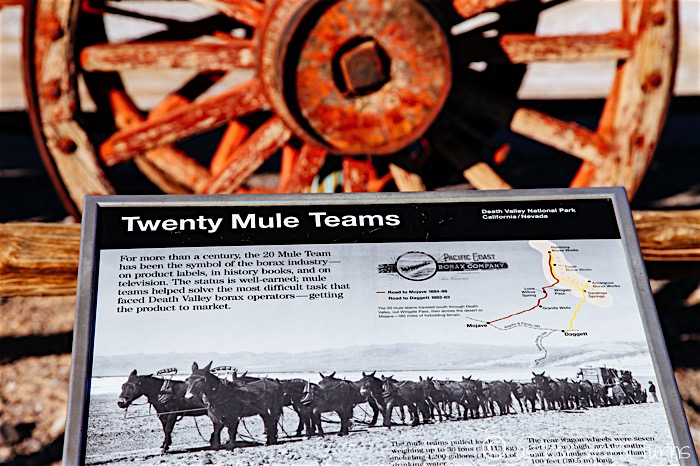

This is the Harmony Borax Works Interpretive Trail. According to signage, borate (salt minerals) were deposited in ancient lake beds that uplifted and eroded into the yellow Furnace Creek badlands. Water dissolved the borates and carried them to the Death Valley floor, where they recrystallized as borax. Over the past 100+ years, this mineral has been used by blacksmiths, potters, dairy farmers, housewives, meat packers, and even morticians.

Back in 1882 a San Francisco businessman named William T. Coleman built a plant here to refine “cottonball” borax found on the nearby salt flats. He recruited Chinese workers to camp here as it was cheaper to refine the borax in Death Valley instead of transporting the pre-refined product 165 miles across the desert. After five years the plant closed; remains of the operation are seen in the photos below.

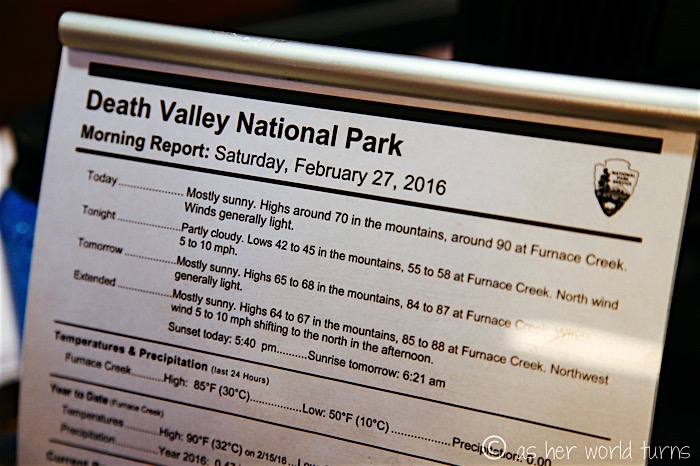

Shortly beyond the Harmony Borax turn-off we approach Furnace Creek, the village at the center of Death Valley. This is where we pay our national park entrance fee ($20 for up to 7 days) and ask a ranger for advice on where the best super bloom stops are (they have a handy map available for free). She also recommends a few short hikes to check out. I’ll detail all of this over separate blog posts the next few days.

At this point there’s only an hour or so before sunset so we head back north to Salt Creek and the sand dunes area, admiring wildflowers and mountains in the distance.

I wish I could condense my Death Valley photos into one giant post, but there’s a lot of pictures so I’ll spread them out over a few days. More tomorrow!