In the past three months I saw ten shows in New York City — three on Broadway, seven off-Broadway. Four musicals, five plays, and one play with music (I’ll explain that distinction in the first review). As a writing exercise and also a way to process / record my thoughts on each piece, I like to write mini reviews and share them here. Hopefully they’ll be of use to anyone looking for recommendations on what to see in the city… although my apologies as many of them were limited runs and have already shuttered. But you can still see Dear Evan Hansen and Jitney, both of which I highly recommend. Plus there is a good chance some of these shows will have more life in them, either on Broadway or regionally.

Without further ado…

Vietgone by Qui Nguyen (off-Broadway)

Vietgone by Qui Nguyen (off-Broadway)

Best show I saw in 2016, hands down. It ran in late fall at MTC and my only regret is that I didn’t see it five more times. The playwright puts his parents at the heart of this story, exploring how they met at a refugee camp in Fort Chaffee, Arkansas after leaving Vietnam during the war. The action cuts back and forth between the lives they left behind in Vietnam and their new reality at the camp in Arkansas. The show begins with a direct address to the audience from the playwright (who is portrayed by an actor) explaining how this play will handle language — the Vietnamese characters talk just like us, speaking in English peppered with present-day slang. The American characters will talk only in a string along nonsensical phrases like “Yippee aye, Captain Crunch, apple pie, home of the brave!” It is a brilliant reversal of stereotypes. Oh, and there are Hamilton-esque hip-hop numbers — maybe five or six in total (Vietgone is not a musical, but rather a play with music). The development of this show predates Hamilton‘s off-Broadway arrival so it’s not a rip-off. The musical element brings this play to the next level, jumping in intensity to match the characters’ place in their emotional journey as they mourn those they’ve left behind and struggle to live in a new, wholly different culture. There’s a bunch of Brechtian distancing effects — breaking the fourth wall, actors playing multiple roles, the addition of musical elements — that compel the audience to examine what Vietnamese refugees went through during this time period. It’s all done so brilliantly and I really hope this show moves to Broadway — given the evolution of commercial theater these past few years, it could do quite well on a larger stage in midtown.

Master Harold and the Boys by Athol Fugard (off-Broadway)

Master Harold and the Boys by Athol Fugard (off-Broadway)

I’ve wanted to see Master Harold and the Boys for years, and this flawless production at Signature Theatre was worth the wait. It’s a three-person play set in 1950 at an empty tea shop on a rainy afternoon in South Africa (where esteemed playwright Athol Fugard hails from; I’ve been to the theater named after him in Cape Town). Two black employees work in the shop, which is owned by a white family — of whom we only meet their teenage son, the titular Master Harold. While Master Harold and the employees (“the boys”) are quite friendly — he grew up while these men lived on his family’s property, and they clearly share a brotherly rapport despite their age difference — the delineation of power is nonetheless clear: the teenage Master Harold holds the reins, and when the situation calls for it, the two black employees must bow down to his wishes. This play asks the question, is it possible to truly break down racial and class barriers when even a child who has grown up surrounded by people different from him has trouble opening his perspective to see them as equals? If THAT doesn’t do it, then what does it take to open people’s minds? As you might imagine, the casting in a three-person play must be calibrated perfectly to capture the balance of these characters, and our three actors are outstanding: Noah Robbins, Sahr Nguajah, and Leon Addison Brown (kudos to all for the spot-on South African accents).

A Life by Adam Bock (off-Broadway)

A Life by Adam Bock (off-Broadway)

I found this to be the most overrated play of 2016. It stars David Hyde Pierce as Nate, a single older gay man living in New York City; after delivering a 30-minute direct address monologue to the audience, he keels over and dies. An affecting sequence unfolds: Nate’s body lies on the floor for minutes, in silence aside from the cityscape sounds outside his apartment. His phone rings, going unanswered. It rings again. The light changes as day becomes night, and then day again. Eventually we hear people outside his door as a friend argues with the super to let him inside. They discover Nate’s body. In what I presume is an accurate portrayal of such an occurrence in NYC, the cops and morgue employees arrive with flash bulb cameras and a gurney / body bag. They insensitively deliver pertinent info to Nate’s friend — who is understandably in shock given what just happened — about how this works. From there on out, we follow the body: as morgue employees chit chat while preparing Nate for the funeral (including a memorable clipping of his toenails) and then the funeral scene, where David Hyde Pierce briefly revives to deliver a closing monologue to the audience. Aside from the silent sequence that immediately follows Nate’s death, I found this play unsatisfying. There is a flashy set change when we move from Nate’s apartment to the morgue, where the set flips backwards on a hinge to reveal the new space. That must have cost a lot. But what do all of these scenes add up to? I didn’t walk away from this theater experience with much.

The Harvest by Samuel D. Hunter (off-Broadway)

The Harvest by Samuel D. Hunter (off-Broadway)

This play opens with characters in the basement of a church in Idaho — we will soon discover that the characters on-stage are training for their roles as missionaries about to go overseas to an unnamed Middle Eastern country. But in the opening scene we have NO IDEA what is going on as they are speaking in tongues, impassionately spewing gibberish and banging on the floor or thrusting their fists at the ceiling. After this fervor dissolves, they move on to their main objective and practice role playing to rehearse their spiels. We learn about them as individuals — a married couple where the wife is more reluctant about this mission and feels misunderstood by her husband, a reserved guy who is anxious about this trip and has some unresolved backstory with his father, and another guy who has lost his parents and whose sister has just returned to town, eager to stop him from leaving on this trip. They are led by a gung-ho advisor who has no problem spinning any situation to show her pupils that the Lord’s way is always right. Playwright Samuel Hunter weaves these lives together in such a believable way; I felt invested in each of them from the start. There are some revelations, all of which feel organic. This is a solid new play and I was very glad to witness it.

Sweet Charity by Neil Simon, Cy Coleman, Dorothy Fields (off-Broadway)

Sweet Charity by Neil Simon, Cy Coleman, Dorothy Fields (off-Broadway)

Charity Hope Valentine, you poor character — even this buzz-worthy revival can’t rescue you from your mid-1960’s fate, at the mercy of gender stereotypes and slut-shaming. I’d never before encountered this show and was only aware of the hit “Big Spender,” so it was a treat to discover Sweet Charity as staged by prominent director Leigh Silverman and starring the luminous, multiple Tony-winning Sutton Foster. It was staged in an intimate setting that worked nicely for the Dance Hall scenes (Charity is a “dance hall hostess,” aka a stripper of sorts). This show is all over the map as Charity bounces between her job and other escapades around Manhattan: she connects with an Italian movie star named Vittorio, befriends a shy and claustrophobic accountant in a stalled elevator, and attends a “Rhythm of Life Church” led by a hippie musician. Sweet Charity is ultimately about an earnest woman’s search for a man who appreciates her, despite her day (night?) job at the Dance Hall. And yet it seems that, in 1966, no man is up to the task — even the geeky and sweet Oscar ultimately abandons her, pointing to her lack of purity as the reason, despite his claims leading up to their wedding that he’s not bothered by it. Every once in awhile it’s nice to dig out an older stage show like Sweet Charity, but time is not always kind to such pieces.

Falsettos by William Finn, James Lapine (Broadway)

Falsettos by William Finn, James Lapine (Broadway)

What a treat to finally see this show, so marvelously revived by Lincoln Center in a sparsely staged, radiant production starring the unforgettable Christian Borle, Andrew Rannells, and Stephanie J. Block. Falsettos centers around Marvin, his ex-wife Trina, and his new lover Whizzer. Plus Marvin and Trina’s young son Jason, Marvin’s shrink (who later marries Trina), and the lesbians from next door. Got all of that? Falsettos was written in 1992 around the height of the AIDS crisis and in terms of historical theatrical significance it could be considered the musical counterpart to Angels in America, which premiered a year later in 1993. It must have been somewhat revolutionary to see this gay love triangle play out on a Broadway stage in the early ’90s, ahead of acceptance on mainstream television. In 2017 it feels totally normal. These actors are quite perfectly cast — especially 12-year-old Anthony Rosenthal as Jason — and it’s a delight to watch them in these roles. Composer and lyricist William Finn’s music holds up quite well; I am particularly taken with “Unexpected Lovers” and “I’m Breaking Down” (check out Stephanie J. Block belting her face off in this performance). Falsettos ended its short run in early January but was preserved in a Live from Lincoln Center production to air later this year.

The Band’s Visit by David Yazbek, Itamar Moses (off-Broadway)

The Band’s Visit by David Yazbek, Itamar Moses (off-Broadway)

This show is a real treat — a new musical that feels so complete and fleshed out and specific, as though its characters truly live and breathe inside this world. It’s based on the 2007 movie of the same name, which I am not familiar with. The plot is relatively simple: an Egyptian police band arrives in Israel en route to perform at a cultural center. But after arriving at the airport, they get on the wrong bus — they intend to go to a city called Pet Hatikvah, and end up in the village of Bet Hatikvah. They stay one night with local residents who kindly take in members of the band, and we get a window into a town where “nothing ever happens.” In some respects, very little does happen in this show, and in other ways, everything happens and both the police band and the town’s residents open up in new ways that will leave them forever changed by this unintended visit. The music is by David Yazbek, and it sounds nothing like his previous work, which is primarily comedic (Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, The Full Monty, Women on the Verge) — the songs in A Band’s Visit exude less energy, instead expressing feelings of longing, wistfulness, and words left unsaid. It was an enrapturing experience and I was reluctant to leave the theater (worth noting: I ran into Sarah Jessica Parker in the lobby at the matinee, and heard from a friend at the evening performance that Sondheim had attended — surely a sign that this is a musical to keep your eye on). Rumors are it may have a life on Broadway at some point — keep your fingers crossed that this gem of a musical will finds its way in front of more audiences.

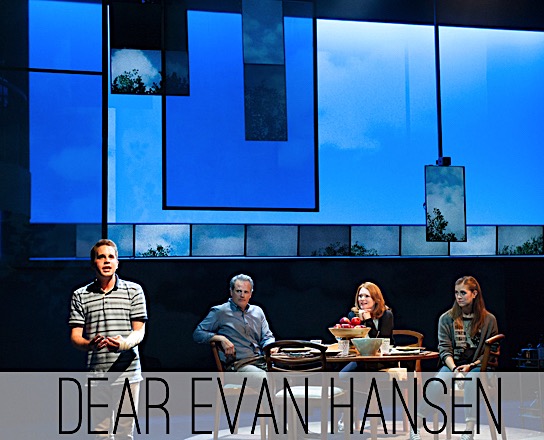

Dear Evan Hansen by Benj Pasek, Justin Paul, Steven Levenson (Broadway)

Dear Evan Hansen by Benj Pasek, Justin Paul, Steven Levenson (Broadway)

Dear Evan Hansen is easily the front-runner for this year’s Tony Award for Best New Musical. It’s based on a wholly original plot about an intercepted letter — Evan is a depressed high school student who has been instructed by his therapist to write self-affirming notes (hence the title), and one of them is intercepted in a computer lab by a loner classmate named Connor who shortly thereafter commits suicide… with the note in his pocket. Connor just happens to be the sister of the girl Evan has a crush on, and when her parents misconstrue the letter as a sign that Evan was good friends with Connor, suddenly Evan finds himself at the center of this tragedy. Evan becomes an honorary member of Connor’s family, much to the dismay of Evan’s mother who works long hours to provide for her son. But Evan’s new life is based on a lie — when Connor’s family finds out that Evan really didn’t know their son/brother, will everything fall apart? The stakes get higher when Evan speaks at a school memorial for Conner and his speech goes viral on social media. The songs are pop-ish and memorable, especially one of the opening numbers, “Waving Through a Window.” Several times while watching this show I was reminded of Next to Normal, another family drama musical that was also directed by Michael Greif. The plot unfolds so naturally, snowballing in a way you never see coming, yet making perfect sense the whole time. Ben Platt is extremely memorably as the angsty and awkward Evan, physicalizing just how uncomfortable he is at every given moment. His voice soars on each number. Rachel Bay Jones is the other stand-out as Evan’s mother in a heartbreaking performance that culminates in an eleven-o-clock number that will leave you bawling your eyes out. This is the show that I am sending everyone who asks me for theater recommendations to see — if you can even get tickets at this point, as it’s selling out every night. Go, go, go — this is the best new Broadway musical of the season.

The Babylon Line by Richard Greenberg (off-Broadway)

The Babylon Line by Richard Greenberg (off-Broadway)

There are some affecting moments in this new play, but I’m not sure the whole adds up to more than the sum of its parts. It takes place in a classroom on Long Island — the title refers to a railroad line that runs from Manhattan to this town — at an adult education class for those who want to learn writing from a struggling novelist who commutes in from the city (Josh Radnor). While most of the classmates are there on a lark — housewives who were turned away from the overbooked flower arranging class and picked writing as their back-up option, an army veteran who only writes about one specific memory from the war, and a dull former jock who has delusions of someday being a novelist but doesn’t actually write anything — there is one woman (Elizabeth Reaser) for whom this class seems to be a lifeline. There is a desperation in her presence, and her writing shows real promise. The play is a series of excepts from these weekly classes, punctuated by direct address from Josh Radnor’s character (as an old man recalling this story from his younger days). The ensemble actors who play other students in the class are just excellent — Randy Graff, Julie Halson, Maddie Corman, and Frank Wood. But in the end… I walked out of the theater no different than when I arrived. This theatrical experience didn’t draw a specific response from me, or cause me to deeply connect to something in my own life, or show me insight into a perspective I hadn’t previously considered. It was a nice way to spend two hours. I just wish this play had more substance.

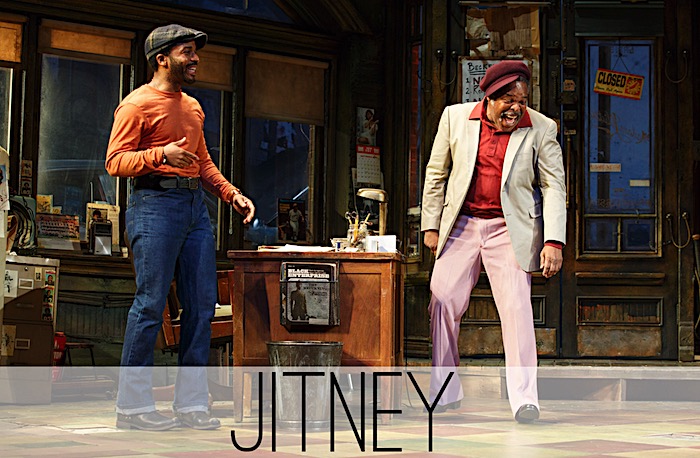

Jitney by August Wilson (Broadway)

Jitney by August Wilson (Broadway)

A stellar production of a lesser-known August Wilson play is currently running on Broadway, and I am so glad I prioritized seeing this show. It takes place in a Pittsburgh cab station in 1977 (it was first performed in 1982) as cab drivers answer the phone line and then leave to pick up passengers — so there is a constantly rotating cast of characters as these drivers depart, return, and depart again. But each driver is distinctive and fully fleshed out, especially as embodied by the excellent actors in this Manhattan Theatre Club production (which include two actors from the Oscar-nominated Moonlight: Andre Holland and Brandon J. Dirden). We learn tidbits about everyone — their home lives, their backstory, who is connected to whom. Is one cabbie cheating on his girlfriend? What will happen when the boss’s son is released from jail after serving his sentence for murder? But the most compelling part of this play is just how relevant it is now, 35 years after Wilson wrote it — his dialogue about race and class feels just as pertinent in 2017 as it did in the early ’80s. Kudos to producers (which include John Legend) for choosing now to bring the only piece from Wilson’s 10-play American Century Cycle (aka the Pittsburgh Cycle) that has never previously run on Broadway.