It’s nearly 11pm when the alarm goes off. The hour of our departure is upon us.

So we’re about to hike to the top of Mt. Kilimanjaro (19,341 feet in elevation). Truth be told, this is nuts — I am underprepared; I have not trained for this. My sister has done several practice hikes on mountains around Los Angeles, but I’ve done nothing because of my travel schedule. So what gives me the cajones / hubris to even attempt this? Past endurance success is a part of it. I ran three marathons back in 2007. I hiked the Inca Trail in Peru in 2009 (13,800 feet), Mt. Whitney in California in 2012 (14,505 feet), and Everest Base Camp in Nepal just last year (18,000 feet). I have yet to experience altitude sickness, which does not preclude me from getting it now, but I know that if I go nice and slow (pole pole) my body tends to cooperate. But the biggest reason I’m giving this a shot is because I know that any endurance battle is largely mental. I am someone who does not give up — short of passing out, I resolve to keep putting one foot in front of the other until I find myself standing on top of a mountain or at the finish line of a race. For better or worse my stubbornness has brought success, and my goal is to employ it one more time.

I’ve also been taking Diamox, which is medicine that helps prevent altitude sickness. (An unfortunate side effect is numb hands and feet, which I’ve experienced here.) My sister can’t take it because she’s allergic to Sulfa drugs, but I’ve taken it once before (Peru) and had no trouble. That said, for Everest Base Camp I took Ibprofin every 4-6 hours the entire time to thin my blood (making it easier for my heart to pump) and sooth muscles, and it worked well. So while I’d recommend Diamox, it’s not necessary if you have another drug like Advil / Ibprofin on hand.

Okay, back to our trek. Here’s a little recap…

After hiking three hours uphill this morning, we spent the day sleeping and eating. Well, we were supposed to, but I got about 2.5 hours of sleep in the afternoon and then couldn’t shut my brain off during our evening nap. Now it’s go time. The chef has prepared hot water for coffee and delivered some cookies to our meal tent. We make a final bathroom run. We add even more layers of clothes — at this point I’m wearing nearly every article of clothing I packed.

We also take precaution to protect our electronics and water bottles, which will freeze at this temperature. I’ve wrapped my water bottles in dirty wool socks (seriously) because we know it’s going to freeze but want to delay that as long as possible; our guide tells us that placing the bottles upside down in our backpacks will help. Similarly, I’ve wrapped my spare camera batteries in socks and store them as close to my body as possible to keep them warm. I tuck my GoPro inside my jacket, also near my body, hoping it’ll still work when we get to the top. My sister has brought along heat packets to put in her gloves; she kindly gives me an extra pair. With headlights strapped to our heads, we’re ready to go.

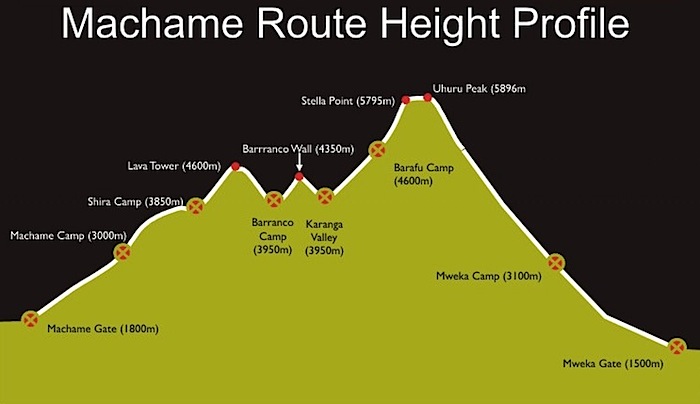

The plan is to hike all night long and get to Stella Point by sunrise at 6:30am. The trail will be steep and unforgiving, but once we reach Stella Point (18,651 feet in elevation) the final push to the summit (19,341 feet) is relatively flat and should take only about 45-60 minutes. Bottom line: once you get to Stella Point, you’ve basically made it, because the last bit is relatively easy. Plus by then the sun should be out and that will warm everything up. This graphic shows just how close Stella Point is to the summit:

[image via]

Just before departure, we take this photo on my iPhone.

Our goal is to leave around 11:30pm but it’s almost midnight when we step out of camp. And camp is beautiful at this hour — tents are illuminated as everyone wakes up, preparing for the big night ahead. There are no clouds in the sky.

I shoot a few long exposures, knowing that I won’t have many photo opportunities in the dark. Our guide Bruce has talked to me about taking pictures; he’s concerned that if I stop too often tonight it will slow me down and the cold will become a bigger issue. I need to focus all my energy on the hike. Fair enough, so I pack my camera inside my backpack (instead of the bag that hangs by my waist for easy access) so that it will deter me from stopping for photos. We’ll pause for a quick break every 45 minutes or so, during which I can take out my camera for a shot or two.

I don’t feel as bad about this as I might’ve predicted — since it’s night, there isn’t much to photograph anyway, aside from a few long exposure shots which tend to look identical after awhile. I get a couple out of my system early on and then take my camera out maybe three times total between midnight and 6am. Since I don’t have a tripod with me (it’s too bulky) I have to find rocks with a flat surface to anchor my camera while I leave the shutter open for around 10 seconds.

There’s no moon and the sky is pitch black except for stars. I wish I could say this is our view for the whole night, but our backs are turned this way as we trek upwards along the path. Honestly, we can’t even see the stars because of our headlamps — and we’re looking down at our feet the whole time, navigating rocks and trying not to fall. So it’s hardly a serene trek under the stars.

But when we take a quick break to drink our (very cold) water and choke back a few bites of energy bar, it’s an opportunity to turn off the headlamps and admire the stars.

Trekking in the dark is a frustrating experience because it feels like we’re not making any progress. All we can see are the dots of headlamps above and below us; since we’re moving about the same speed, it feels like everyone is just marching in place. If there was daylight we could see our progress and feel better. It’s disheartening and monotonous to see the same view for six hours of darkness.

Our guide Bruce was totally right about the camera. Even though I only take it out a few times (how can I not?) it leaves me winded and unprepared for the next stretch of trail. I wish it was possible to take a screenshot of what my eyes are seeing. But those images live in my brain, and it’s too bad I can’t share them here.

This next photo is the longest exposure I shoot all night. That’s Base Camp in the distance. To the naked eye, you can just make out the Milky Way, but with the benefit of manual camera settings we see it more clearly here:

With my camera tucked out of reach, I’ll have to rely on narration instead of photos to document the next several hours.

I wish I could properly communicate just how cold it is. Within the first two hours of hiking — so, by 2am — I can’t feel my fingers or toes. Gradually the cold spreads up my hands and feet, and soon enough I am aware that I’m moving my legs, but they feel like stumps as I take each numb step. Similarly, tasks such as opening my water bottle become increasingly difficult. Using my camera is out of the question, largely because my fingers would have trouble operating the dials and the thought of taking my glove off even for a minute scares me.

The gaiter around my neck is vital. I keep it pulled all the way over my nose so that it acts as a filter for the cold air, and then it traps in the heat of my exhalations to warm my face. It’s like my own ecosystem in there. Probably not the healthiest way to breathe, but inhaling cold air without the buffer of my gaiter is too sharp on my lungs.

I try to conserve energy by concentrating on the ground in front of me; the headlamp helps, acting as a spotlight to focus my attention. I just put one foot in front of the other, trying not to look up or down to avoid the discouraging view of those floating headlamps.

From past endurance hikes, I know that drinking water and eating bites of food regularly are imperative if I want to keep up my energy. Every 15 minutes or so I try to take a sip of water and one bite of a granola bar or energy chew. Our guides are not as keen to stop, but I press them for a quick break (a minute or less) because it takes too much energy to coordinate getting out the water / bar and then chewing while maintaining our hiking pace. I can’t skip those fuel fixes or I’ll pay for it later.

By around 4am or 5am (it’s hard to say as we’re not wearing watches and time seems nebulous at this point), my sister is having a rough time. Not so much physically, although that’s certainly a challenge, but more mentally. Sort of moaning, crying, and a little distressed. Thankfully my frame of mind is still in a good place so I keep her engaged in conversation. It’s our grandmother’s 96th birthday today and I ask her about her favorite memories with Grandma. I ask about her favorite teachers from when we were growing up. And about what countries she’d most like to visit. I share my answers, too, and it’s a nice mental distraction from the task at hand, even if it does leave us a little out of breath.

When the conversation runs out and I can’t think of anything more to ask, I turn to my endurance tricks. That’s right, I have a box of tricks tucked away especially for this sort of occasion, which I pull out during marathons and high altitude hiking, or if I’m feeling lazy at the gym. When my mind and body start to lag, I begin to count steps. Usually up to 100, alternating between English and Spanish. It’s an attempt to distract myself from the marathon or hike, to set my mind at neutral instead of focusing on how I can’t feel my extremities in this cold weather. Today I take it to a new level — I actually count out loud. In the past it’s always been an internal monologue, but today takes more effort to get out of my head so I verbalize the numbers. A few other trekkers pass by but they’re in their own haze so I don’t think they even notice. And then I resort to endurance trick #2, and this time I refrain from saying it aloud — I repeat the entire Fresh Prince of Bel Air theme song in my head, over and over, giving it exclusive focus and shutting out the present. That distraction trick has seen me through three marathons and numerous Turkey Trots.

By now we are hiking through scree, which is loose pebbles and dirt. For every two steps forward we slide a half-step back, and around this time I start to lag behind. Bethany, having trained for this hike, goes ahead with assistant guide Thomas. Head guide Bruce stays with me. Watching me struggle, he makes the most generous offer to carry my backpack for the last hour or so up to Stella Point. (Fact: he ends up carrying it all the way up to the summit and then back down to Base Camp because I am weak and it slows me down, even though it just has my DSLR camera, water bottles, sunscreen, and GoPro.) I owe Bruce tremendously for this, for without his offer to carry my bag, I’m not sure I would have made it.

Heck, even without the extra weight of my pack, it’s still very slow going. In the final half-hour of darkness, I stop to sit down on a rock for 30 seconds. By now my water bottles are frozen and I can’t feel much of anything. My brain starts to go fuzzy from lack of oxygen. So I meditate, briefly. I imagine that all the people in my life who love me are physically carrying up the rest of the mountain. With each footstep, I convince my brain that I’m not doing the work, but that my family and friends are lifting me up, turning their emotional support into physical support as they carry me uphill. It’s somewhat of an out-of-body experience because being entirely present in the moment is too rough, too raw in my current state.

And then something incredible happens — the horizon grows lighter, and I know that sunrise is imminent. It gives me the biggest boost because it means that soon enough there will be warmth, and feeling will return to my hands and feet.

Like a mirage in the desert, the sign for Stella Point emerges in the distance. Until now I did not know if I would make it — I have every intention of pressing through the pain, but if I pass out and fall then Bruce would probably make me turn around… and my effort to maintain consciousness has worked! I wipe away my tears before they crystallize into ice and rush forward in a burst of energy to meet Bethany.

We share a teary hug in front of the Stella Point sign.

It’s around 6:20am and we have about 45-60 minutes of hiking left to get to the summit. Since Beth has already taken a break at Stella Point, she goes on ahead with Thomas while I sit for awhile with Bruce and drink a cup of hot tea. HOT TEA!! Nothing has ever tasted this good. God bless the porter who carried up thermoses and cups so that newly arrived hikers could warm up for a few minutes before continuing on to the summit.

By the way, the first thing I said to Bruce when I saw the Stella Point sign was, “Can my reward be to take some photos?” These views are incredible as the sun prepares to peek over the horizon.

I gulp down a second cup of tea as more hikers arrive at Stella Point. Then Bruce and I press on to the summit.

The light is so soft at this hour. I insist on wearing my camera around my neck (Bruce, bless his heart, continues to carry my backpack).

Finally, we spot the glaciers. I can’t believe how big these guys are in person. Sheets of ice larger than several football fields span the entire top of Kilimanjaro.

That’s Mt. Mawenzi, dramatically poking out above the clouds below.

The final push to the summit is largely flat but there are some uphill sections. And at around 19,000 feet, it’s slow going.

That’s Bruce wearing my grey backpack in the photo below. On either side of the pack are my water bottles covered in (dirty) wool socks for warmth.

Doesn’t it look like the surface of the moon? There’s no vegetation.

Somehow, Bruce spots a guide wearing a blue sweatshirt that reads CONNECTICUT, likely left behind by a trekker. Bruce stops him to ask if I can take a photo of his sweatshirt, because that’s where I’m from. What are the odds? I’m impressed Bruce even caught this, as some of the letters aren’t even visible.

AHHH that’s it — the summit of Kilimanjaro!!

Climbers from all over the world have brought flags or signs to hold at the summit. These particular gentlemen below have brought THREE flags, including one for a charity they’ve raised money for.

Bethany and I proudly pose at the summit. It’s taken real mental and physical fortitude to get here, and part of me still can’t believe we made it.

The light changes minute by minute as the sun climbs higher. The glacier below that was bathed in soft, early morning light an hour ago now stands in bright sunshine.

This glacier is MASSIVE and I’m so sorry we don’t have time to walk closer.

And then it takes me about 3.5 hours to hike downhill back to camp. It should go faster, but once the summit adrenaline wears off I realize just how weary I am. Long stretches of the trail are made up of scree which is best navigated by taking large strides and sliding down the mountain. Bruce has me hold on to his arm while he shuffles down at rapid speed, sort of dragging me along for the ride — we make quick progress this way, but I’m nervous about falling.

There’s Base Camp way below:

I have to narrate the next part because, again, Bruce very kindly carries my backpack and camera. I’m too exhausted to snap photos and all I can think about is taking a nap in our tent. I’m jealous to think that Bethany is probably down there already, snoozing in the sun!

After what seems like an eternity we finally arrive back at Base Camp. It’s lunch, and then I get to sleep for about an hour before we press onward to our next camp.

You might imagine that with the summit trek behind me, the rest of the hike would be a piece of cake, but it takes everything in me to keep going. I’ve had such little sleep in the last 24 hours and my body just wants to rest. Adding to the struggle is the fact that my knees hate climbing downhill — it’s painful and I use knee braces to keep going; the hiking poles that have gotten so little use up to now are suddenly invaluable as they take off some of the pressure.

It takes me four endless hours to reach Mweka Camp. Poor Bruce has to put up with me asking every 20 minutes, “How much longer?” and then I inevitably heave a sigh at his response. Heck, it’s nearly sunset, and not including our lunch break / nap, we’ve spent nearly 15 hours hiking today. Again, Bethany has gone ahead and I wish I could teleport to our next camp. I take my camera out exactly once to snap a photo of this flower:

To recap, since midnight we hiked from 15,200 feet in elevation at Base Camp all the way up to the summit at 19,341 feet, and then back down to Mweka Camp at 10,000 feet. That is insane! I can’t believe the human body is capable of this, even MY human body. I’ve put it through a lot and am so pleased it’s made it this far.

Ever since we began our descent, I’ve had a hacking cough. Turns out breathing in cold air all night — even through a gaiter — is not a good idea for your lungs. Each time I inhale it sounds like I’m wheezing. I’m concerned, but hope that a good night’s sleep will allow my body to reset. After dinner my sister and I retire to our tent and I take two Ibprofin PM pills to really knock me out. I wake up 11 hours later feeling tremendously better.

KILIMANJARO DAY 7: THE END

In the morning we trek the final three hours downhill in the rain. Pouring rain, in fact. This terrain is similar to the jungle-like trek on Day 1, but it’s a different route that descends very quickly — all the way from 10,000 to 3,000 feet elevation in three hours. This means it’s a lot of downhill and, again, my knees groan in pain. But I use my iPod nearly the whole time and it feels good to have the summit day behind us. I can relax and reflect as we cruise downhill with little effort.

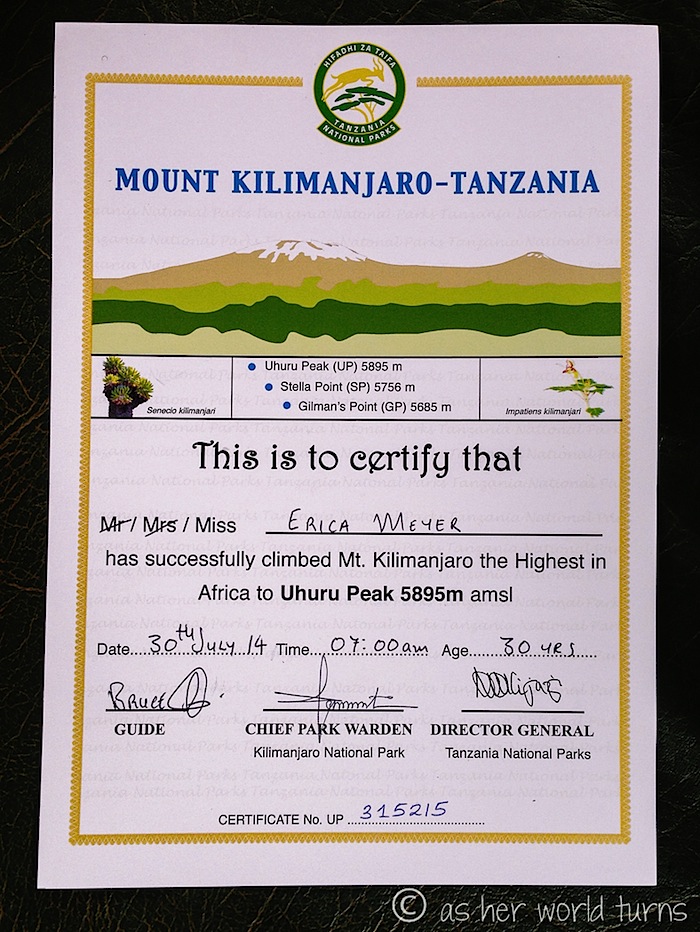

Upon reaching our exit point, we are presented with an official certificate:

A Zara Tours bus picks us up shortly thereafter and we drive about 45 minutes back to the Springlands Hotel in Moshi. A guy sells Kilimanjaro t-shirts on board to the newly accomplished hikers (excellent strategy, buddy) and I buy one. I almost never get t-shirts or souvenirs when I travel, but one features a map of the Machame route and I just can’t pass it up.

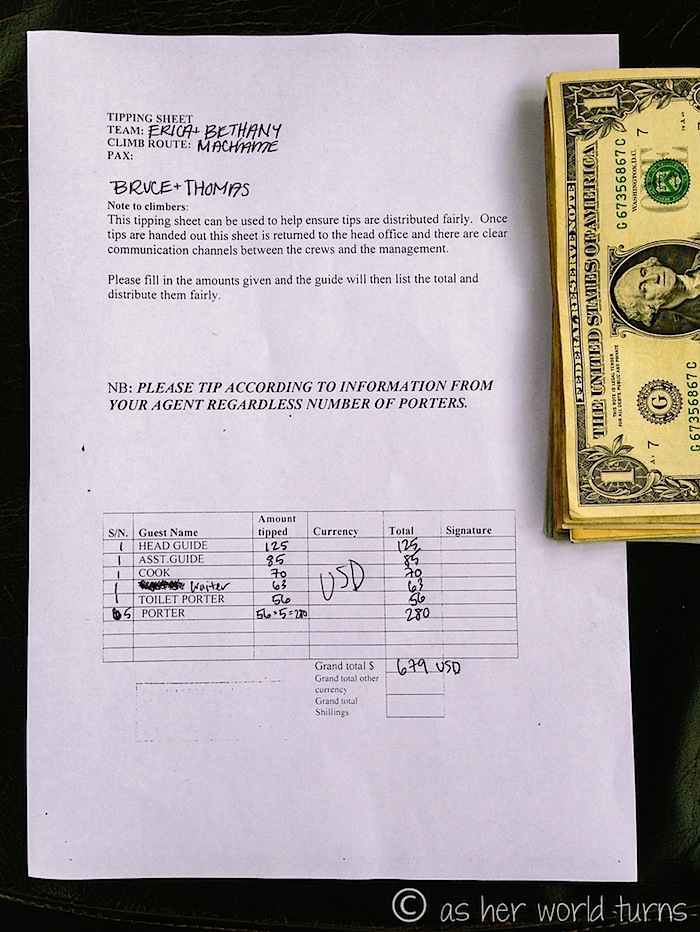

Once we arrive back at the hotel, we have to sort out a final detail — tipping. It’s a frustrating process because I’ve read such a variety of information on-line, and each tour operator suggests different amounts. Tipping is expected and every person involved in our trek needs to be considered. For example, $6-8 per day per porter, $9-10 per day for the cook, $15 per day for the head guide, etc. — all split between each hiker in the group. I had budgeted $250 for this, but upon closer examination of Zara’s guidelines (amounts on their confirmation email conflicted with the numbers on their website), my sister and I realize the minimum we should each contribute is $300, if not more. Had we hiked with more people (which I’d requested but there was no guarantee), the amount would have been a little lower. My sister and I go back and forth on this. I can’t bring myself to tip over $300 since that is already $50 more than I’d budgeted, but my sister wants to be more generous and tips $379 (a number arrived at based on how it’ll be split among the porters/guides). I wish this were a more open process with standard dollar amounts. As we eat lunch, a couple next to us is going through the same process, looking at different tipping guides and trying to reconcile what is expected and fair / generous. I’m intentionally being very open about it here because I want to dispel some of the mystery about what to tip. I’m not saying our numbers are perfect, but if you’re heading to Kilimanjaro, it can serve as one tipping example. And to be clear, these are just tips; every person on the team is paid by Zara for their services.

To conclude, Zara Tours is an excellent company and I would not hesitate to recommend them. From our initial email contact, they patiently answered all of my questions in a prompt manner; their customer service is excellent. They operate out of the Springlands Hotel in Moshi and provide everything on-site — equipment rental (we rented hiking poles and waterproof bags for our belongings), luggage storage for the duration of our trek, meals on-site, a pool, post-trek massages, a $2 bus ride into town, and clean rooms. Our guides, Bruce and Thomas, were top-notch. And our support team — chef, waiter, porters — were all kind and did everything well and quickly. Finally, Zara’s prices are good. I had priced out tours with lots of different companies prior to our trip and Zara’s were among the most competitive. Not only that, but some of the larger travel companies outsource their trips to local professional operators like Zara, so by booking directly we cut out the middle man. We found Zara because friends of ours had used them previously and highly recommended them. I’m happy to do the same after our successful trek.

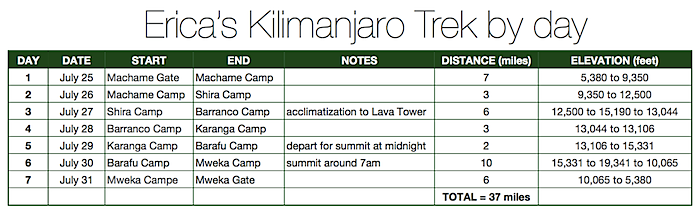

Here is a breakdown of my day-by-day Kilimanjaro stats:

(Thanks to this site for the mileage / elevation info.)

If you missed a post, here’s everything I’ve written so far about our Kilimanjaro trek:

- Kilimanjaro at a Glance

- Kilimanjaro Day 1: Jungle Walk

- Kilimanjaro Day 2: Above the Clouds

- Kilimanjaro Day 3: Lava Tower

- Kilimanjaro Day 4: Barranco Wall

- Kilimanjaro Day 5: Within Reach

- Kilimanjaro Day 6: The Summit

- Kilimanjaro Video Diary

And tomorrow I’ll share one final recap, a video diary of our hike. You won’t want to miss it.

Many thanks to Zara Tours for discounting my Kilimanjaro trek in exchange for photography and blogging. Opinions are my own.

Thanks for sharing your adventure.

Thank you, Mr. Wing! Merry Christmas to you and Ellen too!

Hi Erica,

Just read your post and wanted to comment about the tipping. The tipping sheet doesn’t look that far off from ours. It does look like they recommend tipping the porters alot more and because there are so many of them, it makes your total tip amount alot higher.

Our tipping guidelines are here (http://www.peakplanet.com/tipping-on-kilimanjaro/) if you wanted to compare. We tell our clients to bring about $200-$250.

Thanks for chiming in, Ken! I’m glad this sheet looks like yours. I anticipated tipping $250, but really $300 was the lowest fair amount once we poured over the various tipping guidelines. It was worth it for the high quality guides, chef, and porters though, they really did a stellar job on the mountain.

Out of all the blogs and articles I’ve read about Kili, yours has certainly been the most helpful! I will be attempting the summit next week and still cannot fully grasp what I am about to do. Thanks so much for sharing!

Sieda, thank you so much for your comment! I’m so glad you found the post helpful. I wish you a fantastic experience on Kili and a successful climb to the summit! Good luck!!

Hi, Erica,

thank you for sharing this great adventure and useful information. I’m interested of what camera did you use to take your great shots during the trek to Kili and how managed to charge batteries 7 days without electricity? I saw a Go Pro, but what model was your main camera? I plan to trek EBC next year and there is a same problem… I’m trying to figure out how to charge all my electronic devices for 15 days, without paying the big prices in every hut on the way. Any advices for the both treks, I share the same passion for photography

Thank you for the kind words, and good question! I brought my Canon 5D mark ii, with two lenses: 24-105mm and 15mm fish-eye (here’s more info about the photography gear I travel with). This was a heavy amount of gear, but it was important to me to bring it for photo opportunities. I carried this same equipment with me when I hiked EBC in 2013. For both Kili and EBC, I traveled with two Canon-brand batteries (not the knock-offs) which usually hold their charge for three full days each (in my experience). That lasted me for all six days on Kili, but for EBC I paid extra to charge the batteries at a tea house to make sure that I had enough juice to go for all 12 days. For both EBC and Kili, I put the batteries at the bottom of my sleeping bag at night to keep them warm so they wouldn’t lose their charge quickly due to the cold weather. I also brought a GoPro for Kili and my little point-and-shoot (for video) on EBC; I paid to charge the point-and-shoot battery once in a tea house on the EBC trek. I think I paid something like $2 to charge the batteries, which was worth it. It costs a little more the higher up the mountain you get. Since the Canon-brand batteries are somewhat costly, I made do with just the two of them and paying to recharge when necessary. Hope that helps! Good luck with your trip!