We spend our morning in Kande Beach touring the village. The plan is to visit local homes and then the primary school and hospital. I’m skeptical at first — this smells like a tourist trap — but it ends up being more genuine (I want to say “authentic” but that’s a pretentious word) that I anticipate. I’m really moved by what we encounter today and I’ve looked forward to sharing this post with you all for some time.

Our local guide warns us to be prepared when we exit our campground… there are young men from the village who want to accompany us for the whole tour. They are not looking for money, but want to practice their English and maybe try to sell their artwork at the end of the tour. It’s up to us if we want to engage; there is no pressure to talk to them or to purchase anything. But it is indeed overwhelming! As soon as we walk through the gate, the young men partner up with us (usually two for each tourist) and introduce themselves, asking to practice their English. My plan is to wave them off but they are both persistent and polite, so it seems rude to keep ignoring them. After about 15 minutes I give in and the three of us chat for the remainder of the 2-hour tour. I tell them early on I will not buy anything (I have a ‘no souvenirs’ policy; I simply have no room to carry them, and I’d rather spend money on experiences) but if they want to practice English then I’m happy to converse. They prove to be quite curious and we have some enlightening exchanges.

Here’s Renate and her escorts:

We’re also accompanied by a flock of local children. They immediately latch on to our hands, content to walk the whole way with us.

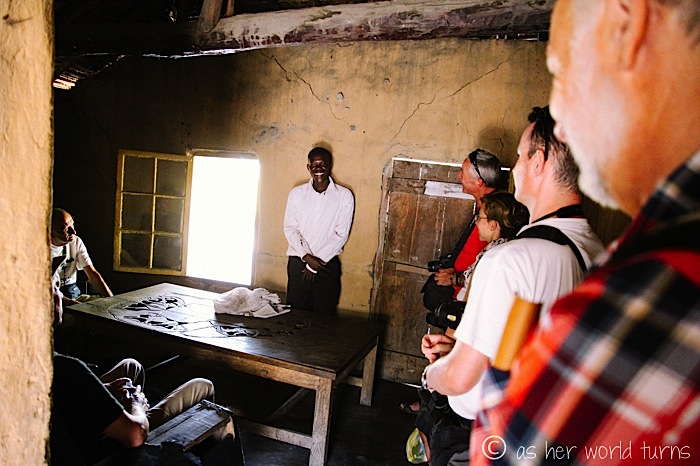

The man in the white shirt below is our local guide, Banjo. He lives in the nearby village with his wife and young daughter; he leads local tours for the overland trucks that pass through. He’s quite knowledgeable and very happy to show off his community.

Chickens live in this elevated platform:

The kids happily pose for pictures, eager for the photographer to then flip the camera around and show them the shots. It’s a neat way to engage with them.

There are several water pumps in this community. This is how all villagers access clean water.

Cassava is a popular root plant in Malawi, sort of like a potato or yucca. It’s starchy and the main source of carbohydrates for locals. This woman sifts through a large pile, peeling cassava one by one.

Cassava grows underground in these dirt piles:

They are harvested out of the ground, but have a dirty skin that needs to be removed.

The woman we just met shows us how she peels off the skin.

And then the cassava dries out in the sun for a period of time before being used for cooking.

A few more local kids…

This is our tour guide’s daughter; she has the biggest smile:

This little boy is the happiest of the whole bunch. He also happens to be deaf. His laughter is so genuine and I can’t help but feel immediate affection for him.

Banjo very kindly shows us his home.

One of the bedrooms:

Throughout Africa I am so impressed with the flora. We encounter a few beautiful plants on our walking tour:

By this point we are comfortable with the young men who surrounded us at the start of the tour. Conversation flows as we exchange stories about our schools, jobs, and apartments / homes. I downplay my backstory a bit, attempting to mitigate my guilt for the abundance of privilege in our Western lives compared to their rural village upbringing. But I don’t want to undermine what they do have — modest shelter, some schooling, and deep family ties. When I tell them I only see my parents a few times a year, they are shocked. They live with several generations under one roof and can’t imagine being separated from family. What these young men lack in material wealth (and certain basic needs like quality health care) is made up by abundant and flourishing connections to their family and neighbors. It’s tough to get a job here, but they have their sights set on being an accountant or teacher. Both are artists in their free time, creating paintings to sell to tourists.

Meet Slim and Nelson, my new friends:

We spot these women below — they come carrying bundles of wood from higher ground, hoping to exchange it for fish from this lakeside community.

Brick-making is a common trade here — they shape the mud with a wooden mold and then fire the bricks in the homemade kilns below.

A young man packs the mud into a wooden mold:

And then carefully sets it to lay in the sun.

This family is very kind and happy to pose for photos.

My tour mate Klaus took the next two photos, for which I am grateful!

We pass through the village’s main road en route to the school and hospital.

We pass through the village’s main road en route to the school and hospital.

Approaching the primary school:

It’s Saturday so school is not in session, but the gathering of young kids who have been with us from the start of the tour are happy to show off their place of learning.

Some of the kids insist on posing with funny faces:

The principal meets with our group to share info about his school. They have 1500 students (ages 5-13) and only fifteen teachers. Can you imagine? The classroom ratio is supposed to be 60:1 but because they don’t have enough classrooms, teachers, or money to pay the teachers, the ratio is 100:1. School is free to kids in this age bracket (although beyond age 13 they must pay to attend private secondary schools in larger towns) and teachers are paid by the government.

While this room has chairs and a desk and bookshelves, the other classrooms only have chalkboards. Students sit on the floor, which is coated in dust and dirt. The walls are concrete and the air is humid.

This is an example of the school uniform — a white shirt and blue dress for girls. The uniforms are important because they remove status and insecurity, putting everyone on the same level. Each uniform costs $10 USD (not including shoes).

Because government funding is quite limited, the school also operates on donations. This is why they are so eager to show tourists the school here — any donated funds go to pay for pens, pencils, and books, as well as to supplement the cost of uniforms. There is a donation box in the room and they stress that it’s not compulsory, no one has to donate. But after sitting in the classroom and witnessing their efforts first-hand, everyone in our group feels compelled to give something. Elisa, a woman from Italy on our tour, has brought pencils and notebooks for the classroom.

Should you be interested in donating supplies, here is the shipping address for the school:

The Headteacher

Kande Full Primary School

P.O. Box 7, Kande

Nkhata Bay

Malawi

Central Africa

They also need monetary donations but it’s unclear if there’s a safe way to send it, with certainty that it would end up in the right hands. So perhaps stick with mailing supplies if you feel inclined to make a difference in the lives of these kids.

Just down the road from the school is a local hospital / clinic. It provides services for around 20,000 people in the surrounding areas.

Our guide explains that new mothers stay in the hospital for 12 hours after giving birth, and then return seven days later with the baby for a follow-up. A woman delivered her baby last night and went home this morning, and during our visit we didn’t encounter any patients.

We pass by the main road with shops en route back to camp.

A herd of horses runs past — we’re told these are the same horses you can hire to ride along the beach at sunset. Two members of our tour do this and rave about the experience; their photos are beautiful.

Back at camp, I say good-bye to my new friends Slim & Nelson and thank them for the conversation.

Major thanks to blogger Tarynne at Away 2 Travel — she did a lovely write-up from her visit to Kande Beach in 2013 and the details she recorded helped jog my memory while writing this post.

I visited Kande Beach on a 30-day Nairobi to Joburg tour with Nomad Tours. They discounted my tour in exchange for blogging and photography; opinions are my own.