This is a sobering post.

Our group spends several hours at the Genocide Museum in Kigali, Rwanda.

I pay the photo fee ($20) to take pictures inside so that I can document the visit here on my site. Most of the info below is shared via photos, but before we begin here’s a Cliffs Notes version of what took place in this country merely twenty years ago.

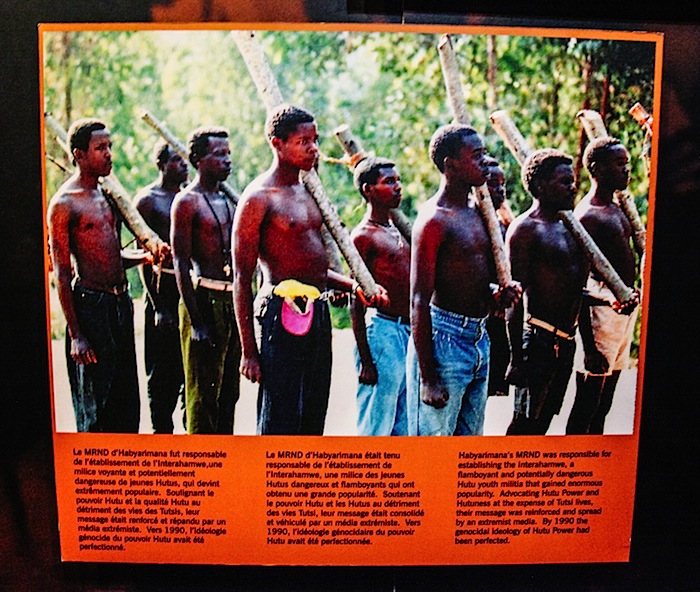

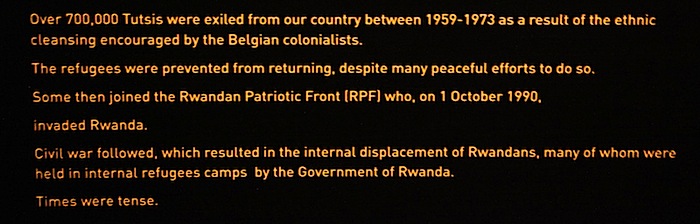

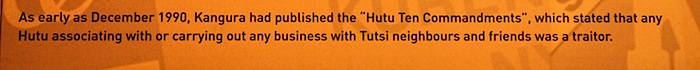

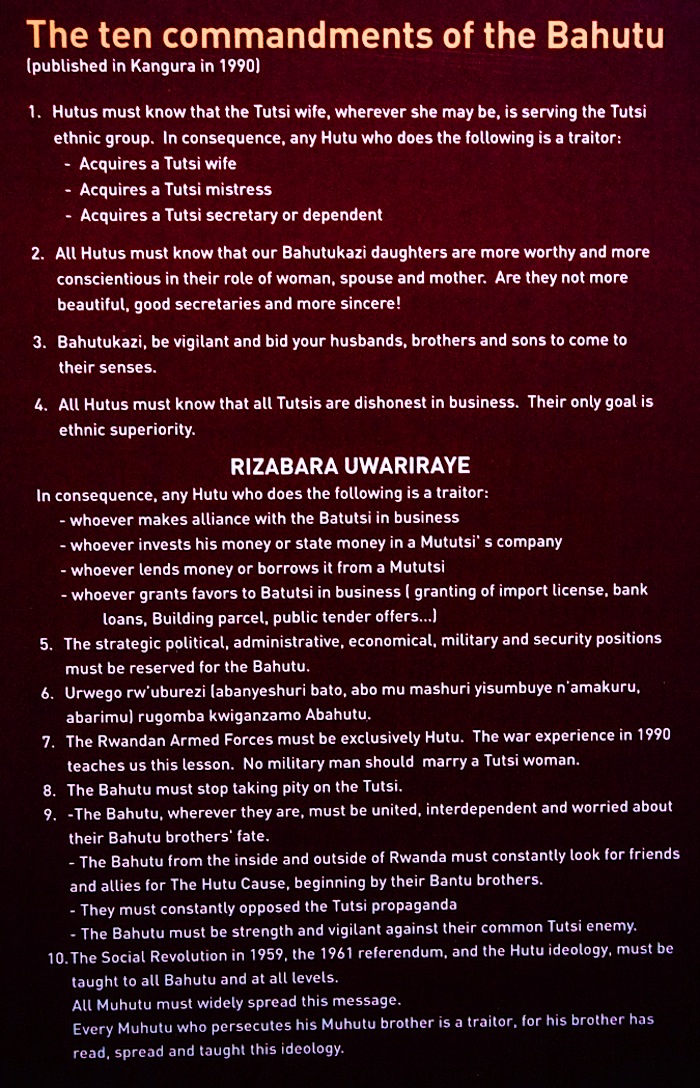

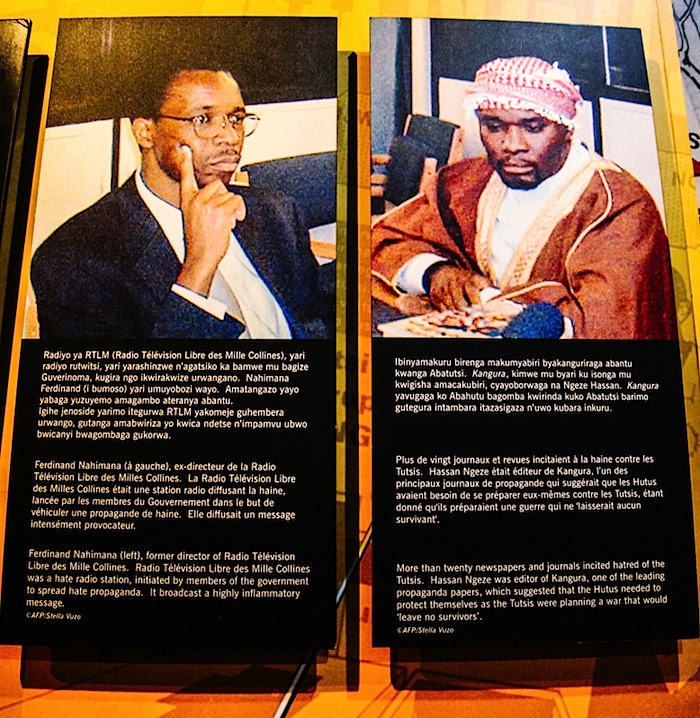

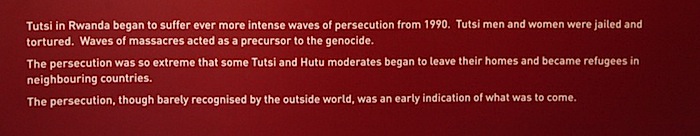

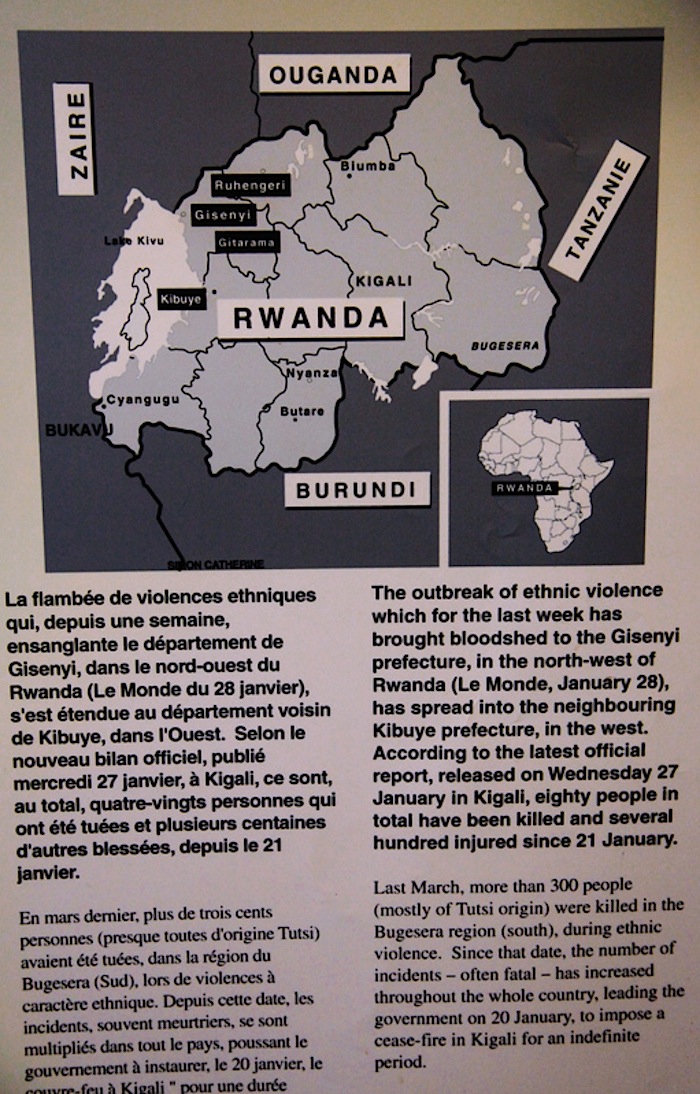

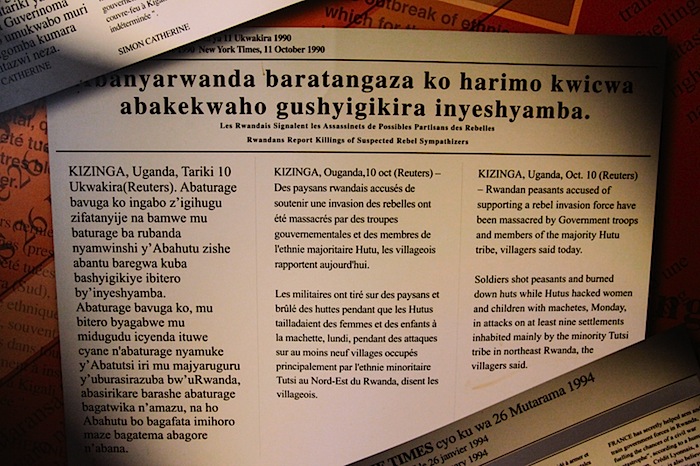

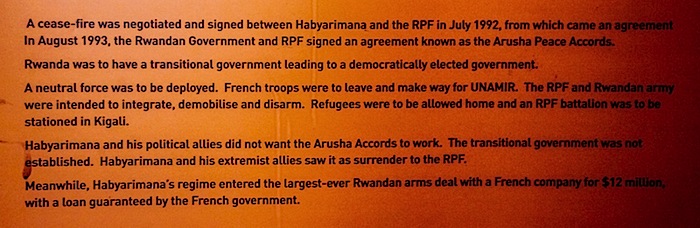

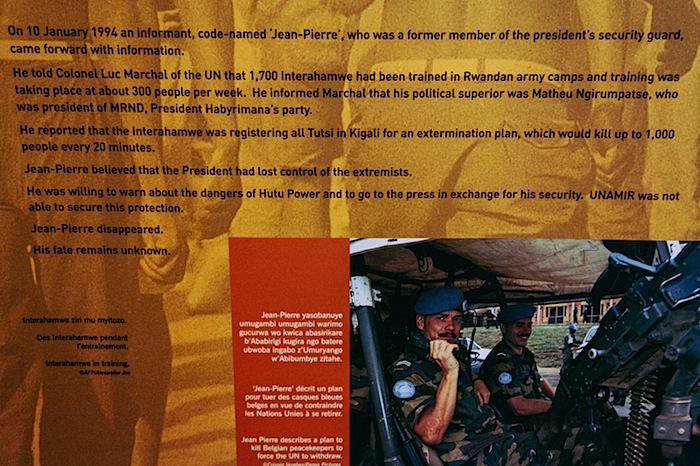

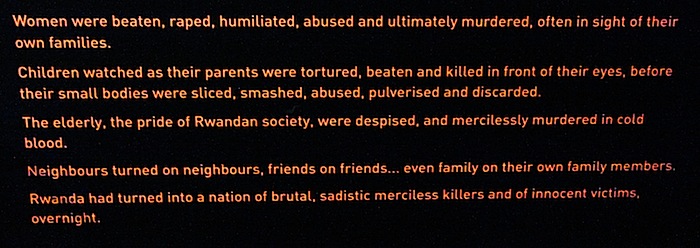

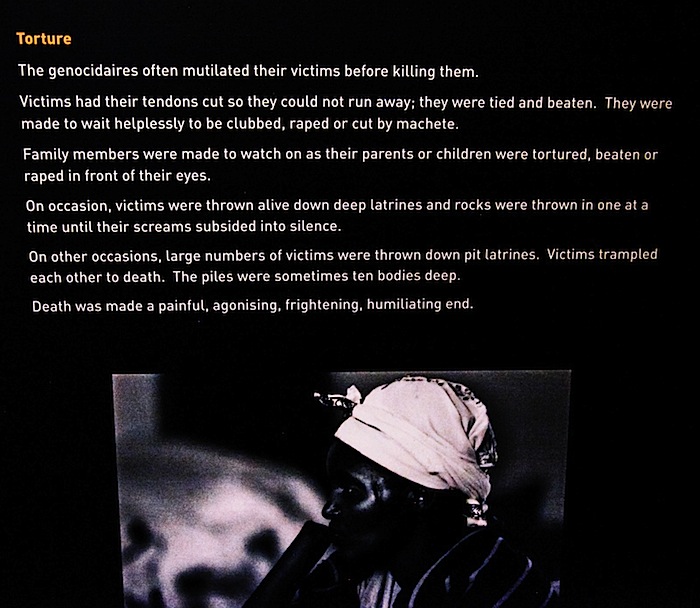

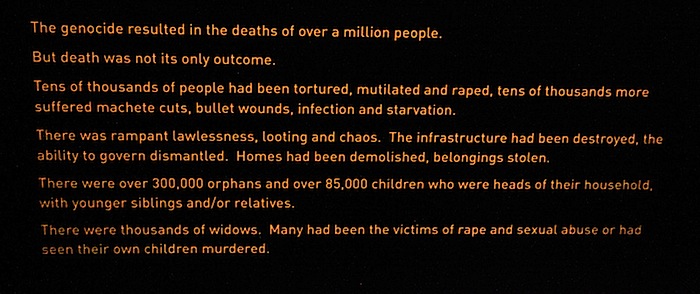

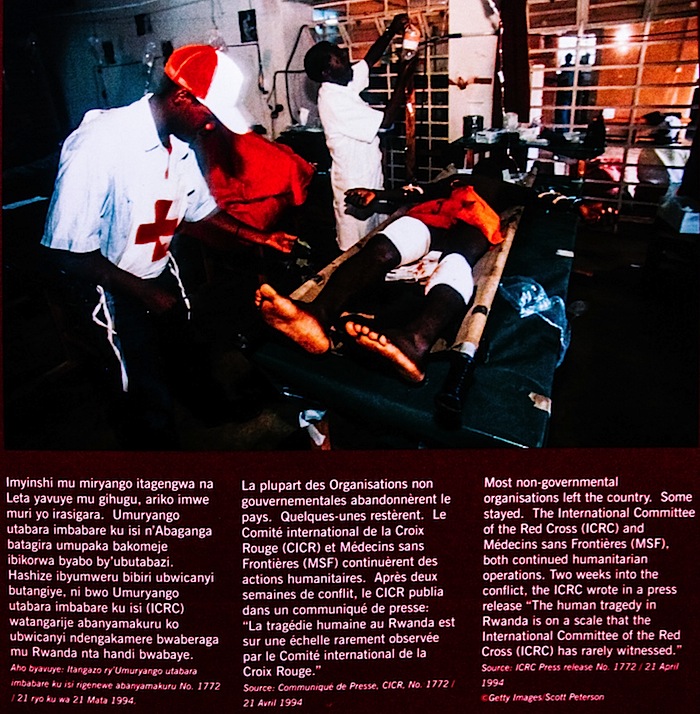

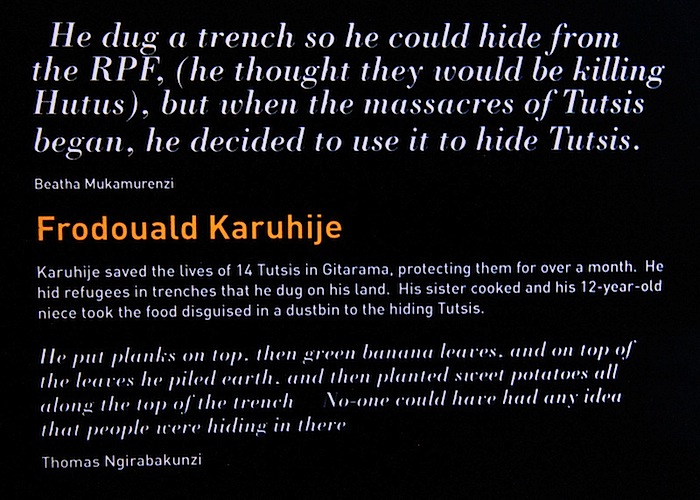

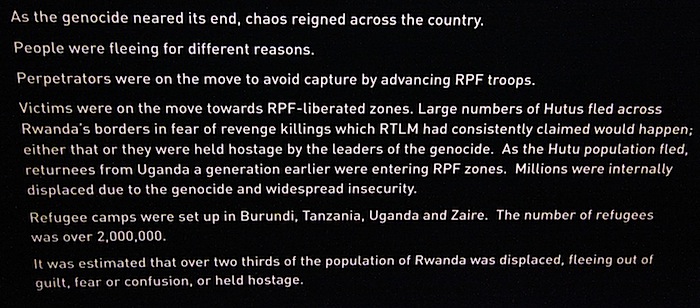

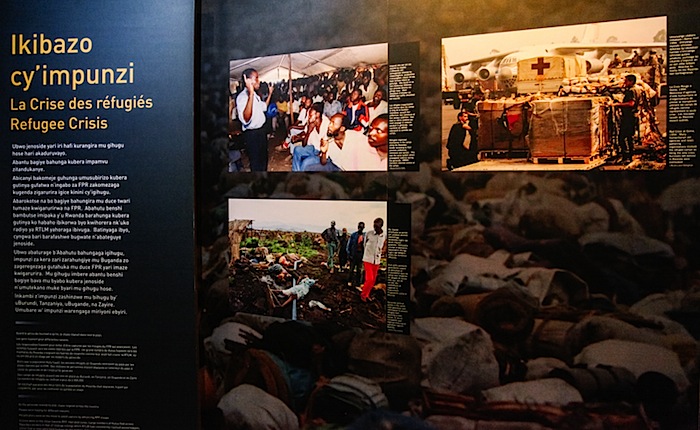

The Rwandan genocide refers to the mass slaughter of Tutsi people by members of the Hutu majority. It happened over 100 days from April to July 1994, during which around one million Rwandans were killed, or about 20% of the country’s population. Of those killed, about 70% were Tutsis and 30% were moderate Hutus. The genocide was planned by the akazu, the political elite, which was largely made up of Hutu members. It took place within the context of the Rwandan Civil War which had begun in 1990 led by the Hutus against the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a group comprised of Tutsi refugees whose families had fled to Uganda following earlier waves of violence against their people.

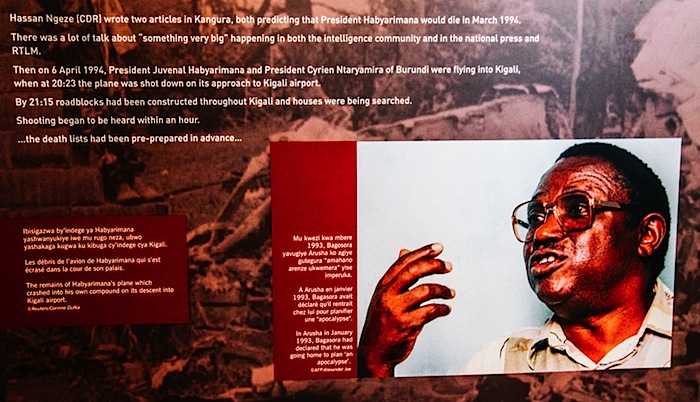

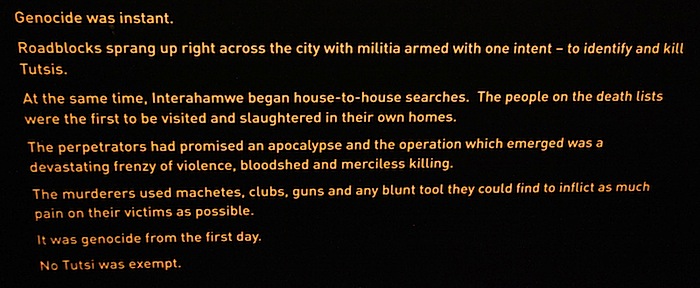

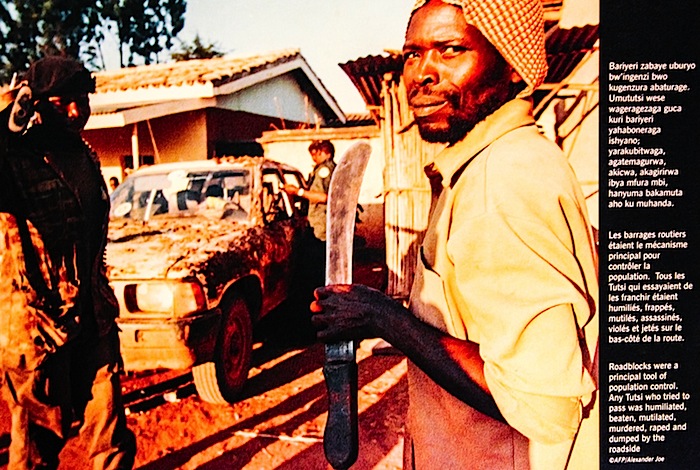

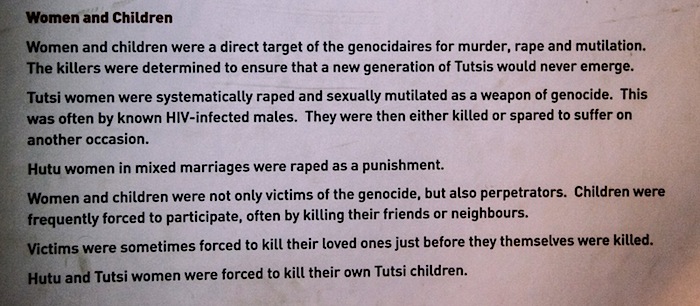

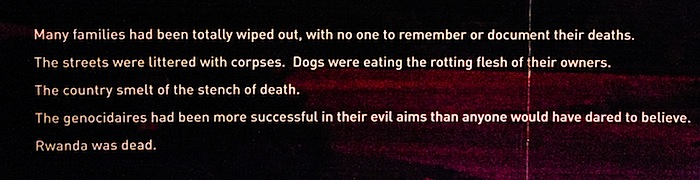

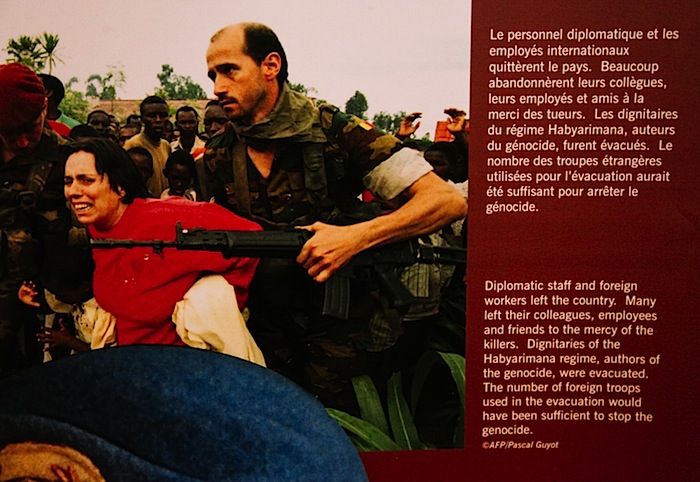

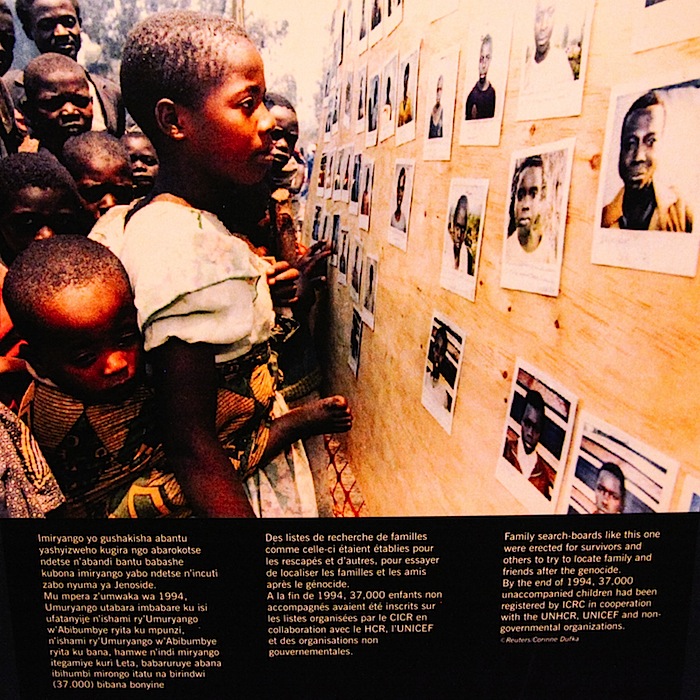

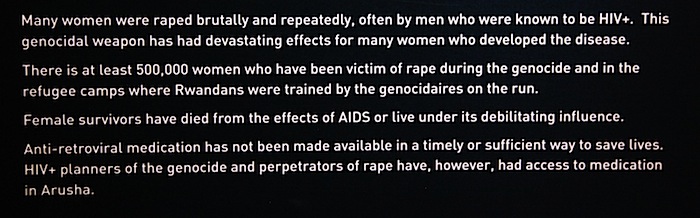

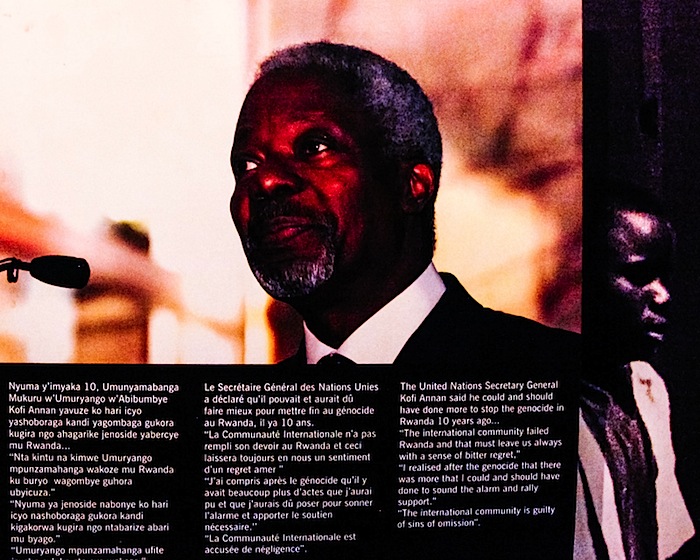

The genocide was triggered on April 6, 1994 when a plane carrying the Rwandan and Burundi presidents was shot down. The next day, key Tutsi members were executed and barriers were set in place to systematically eradicate the remaining Tutsi people. The Hutu population was encouraged to carry weapons and kill their Tutsi neighbors. HIV-infected males were encouraged to rape Tutsi women. By July, the RPF gained control of the capital Kigali which brought the genocide to an end. United Nations and countries like the U.S., Great Britain, and Belgium (who had colonized the nation in prior decades) were criticized for their inaction. The destruction of infrastructure and blow to the country’s population set Rwanda into an economic depression.

(Thanks to Wikipedia for providing those numbers and dates.)

I’ll walk through the timeline of this exhibit so that you can experience the museum for yourself. In lieu of going to Rwanda to see it in person, this is the next best thing.

I did not use my watermark on these photos (they clutter the text-laden images) and I cropped the pictures to show only vital information.

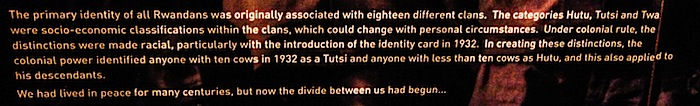

Did you catch that? In 1932, the entire basis for deciding whether someone was a Hutu or a Tutsi depended on how many cows they owned. And the identity applied to their descendants. Seventy years later, that distinction marked the difference between who lived and who died.

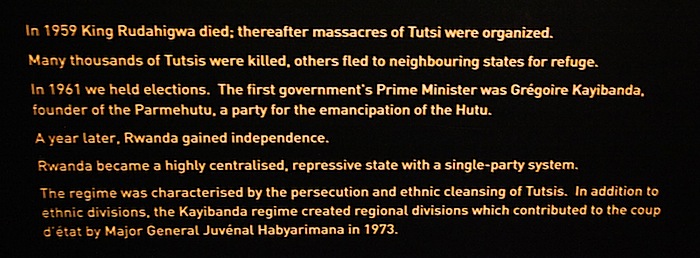

YIKES. This does not bode well.

The death of the Rwandan president was an immediate trigger for the genocide.

The stained glass artwork below is called ‘Windows of Hope’ depicting steps leading to the future.

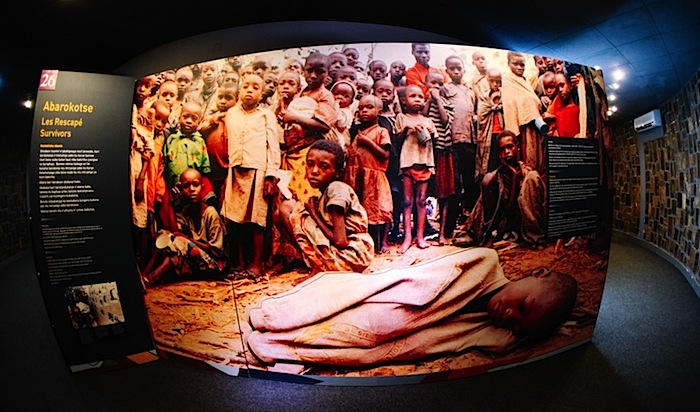

That’s the conclusion of the main exhibit. It’s a lot of disquieting and heart-rending information to take in — how could humans have turned on each other in such a brutal, heinous way?

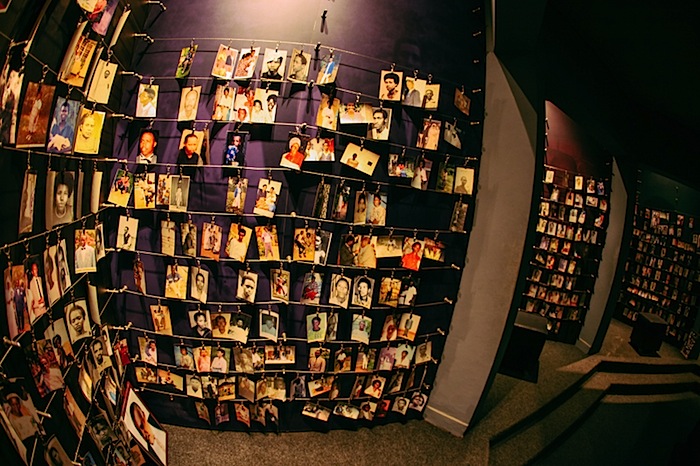

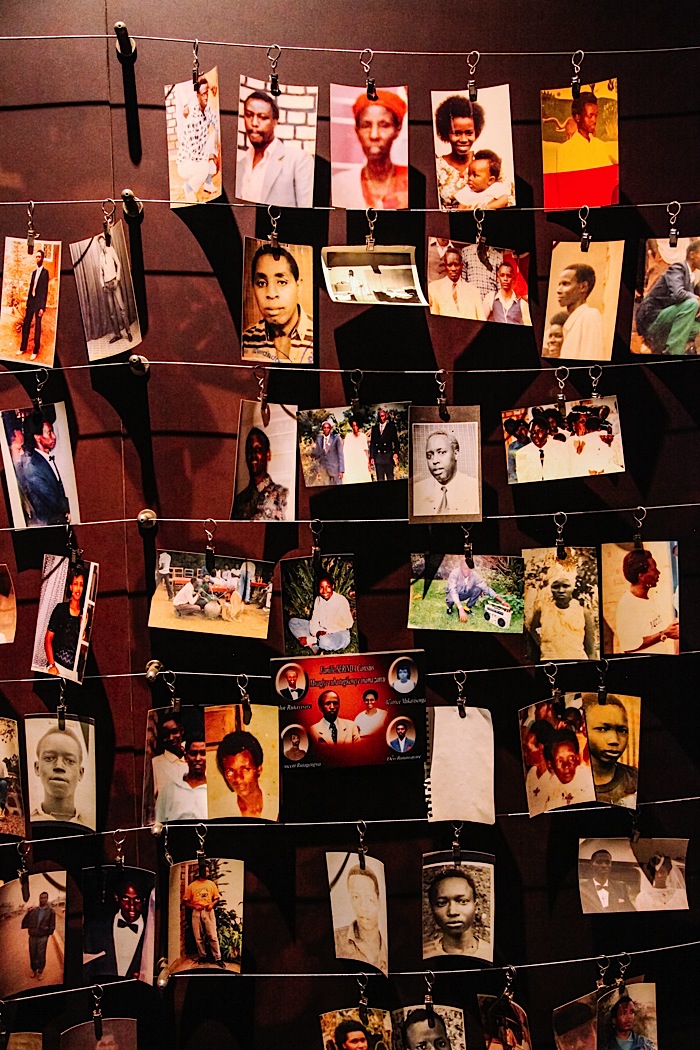

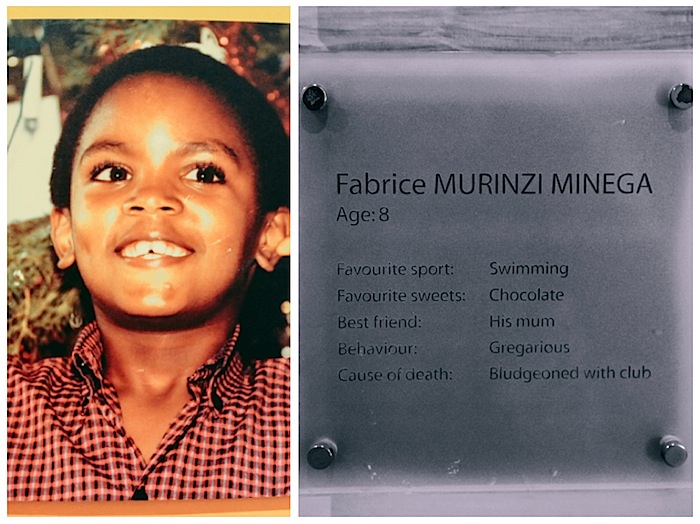

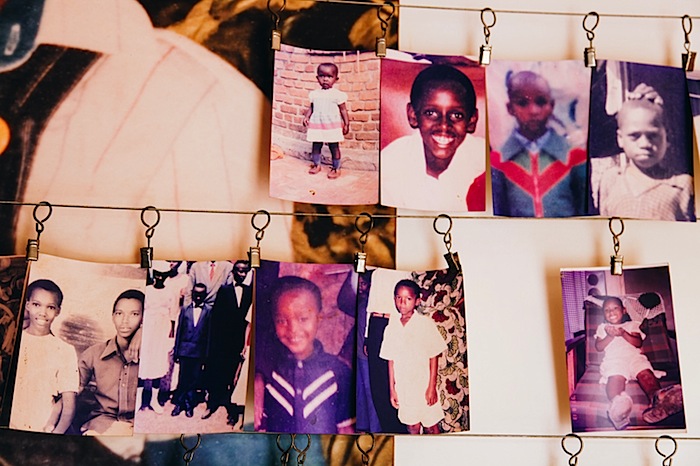

An entire gallery is dedicated to photos of the victims.

These statues in the main chamber depict three phases: before the genocide, during the genocide, and after the genocide. They are made from regional wood and carved and sanded by local craftsmen.

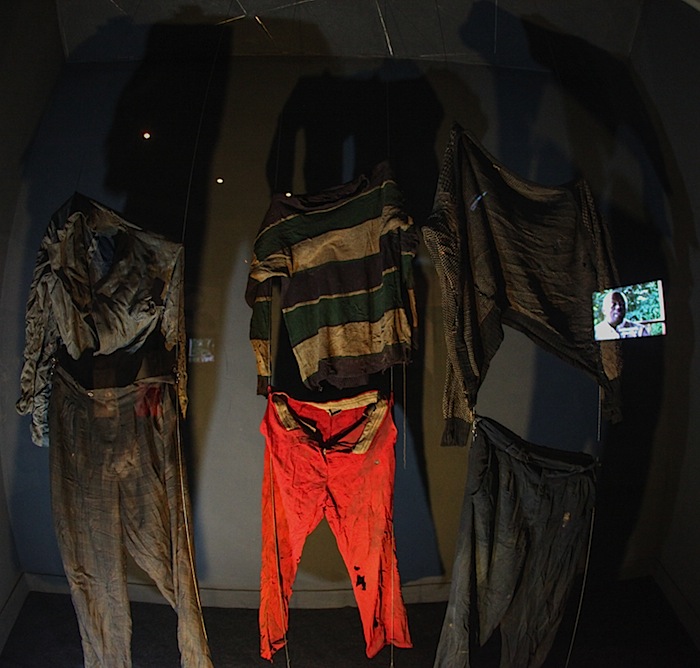

This room displays clothes worn by victims when they died.

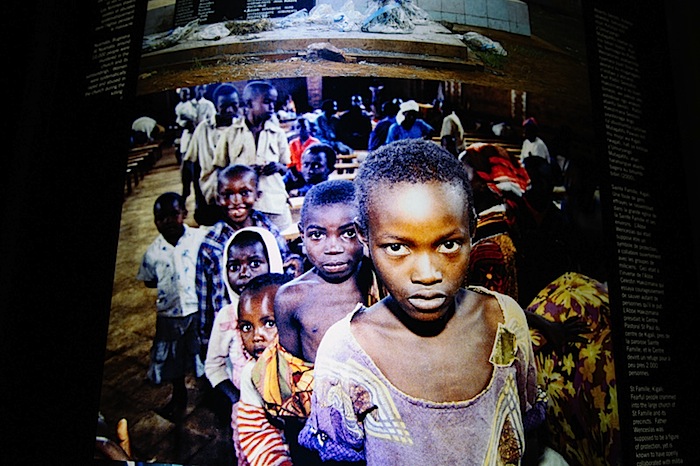

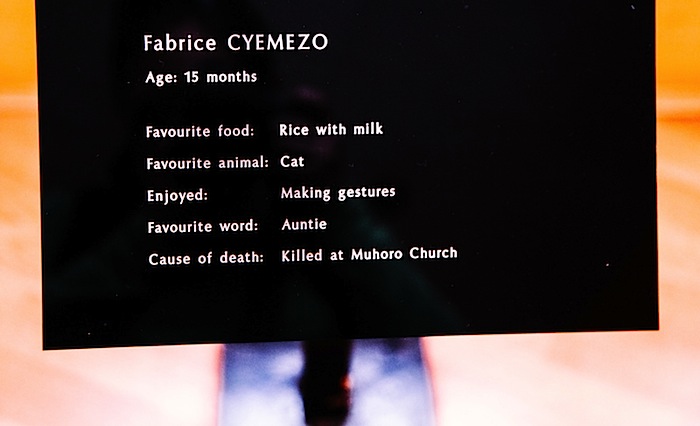

The children’s memorial, on the second floor, is especially heartbreaking. Some members of our group skip it entirely because it’s a gut-wrenching experience from the moment you walk in.

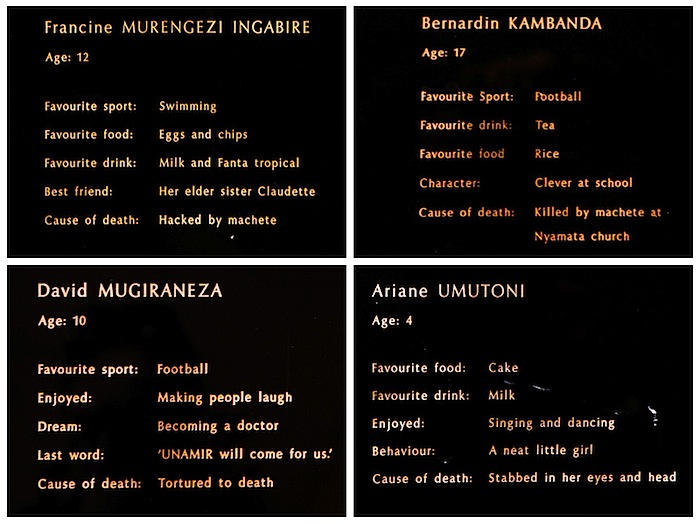

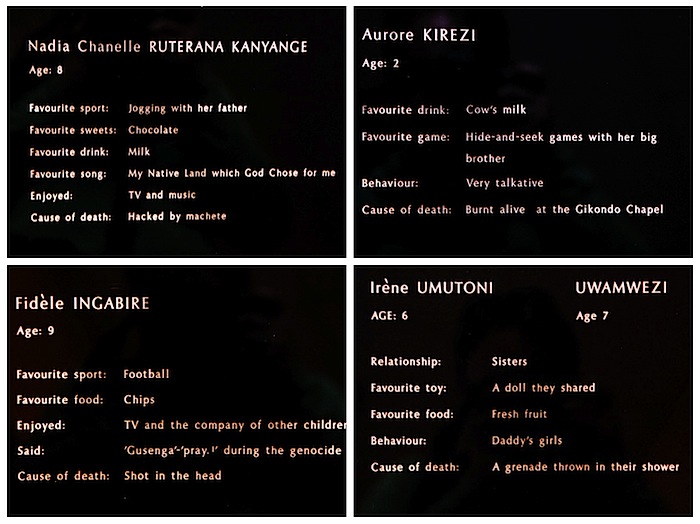

These plaques accompany photos of various children who were murdered during the genocide, along with heart breaking comments about their favorite foods, favorite sports or animal, and the way they died. There are dozens of these displays.

Like the gallery in the main exhibit, there’s another one just for the children’s memorial.

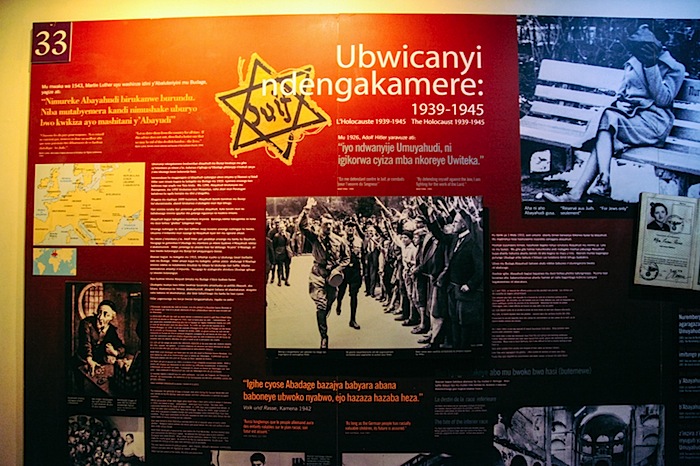

There is one last exhibit that is very much worth visiting, but by now I’m running out of time and have to rush through it.

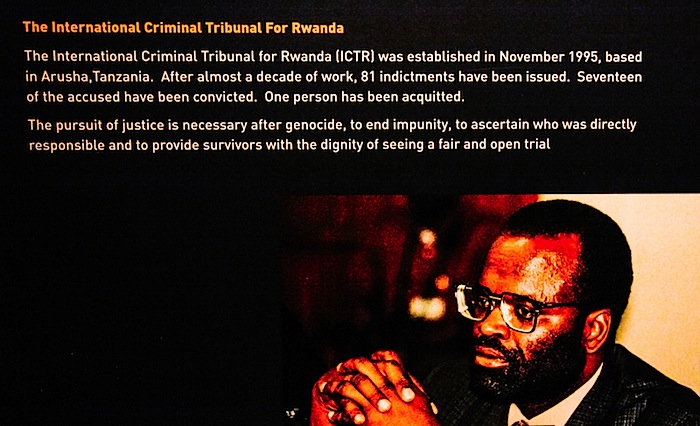

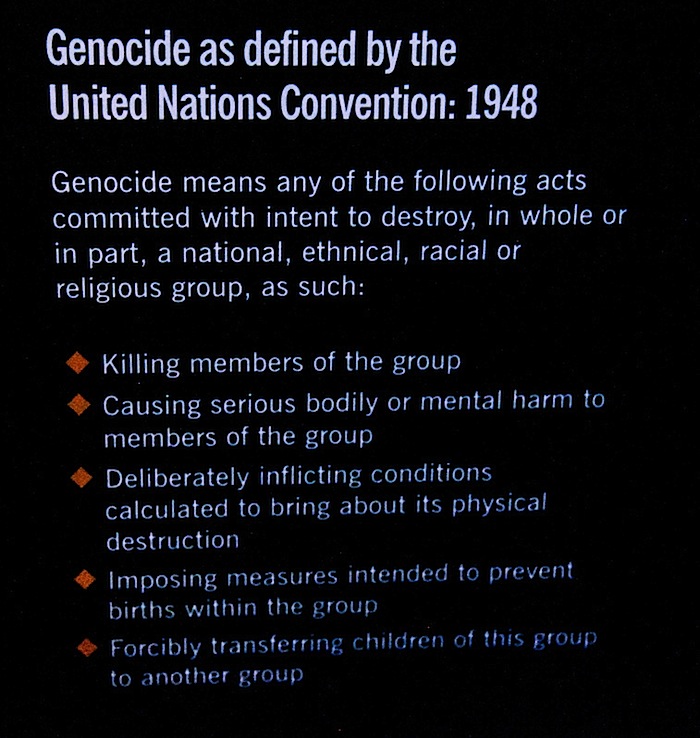

It’s an exhibit documenting genocides that have taken place throughout human history, which in the last century alone includes the Holocaust, Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge regime, ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, and most recently the mass slaughter in Darfur, Sudan.

Our time in nearly up but I take a quick lap around the perimeter of the grounds. Here’s a view of Kigali:

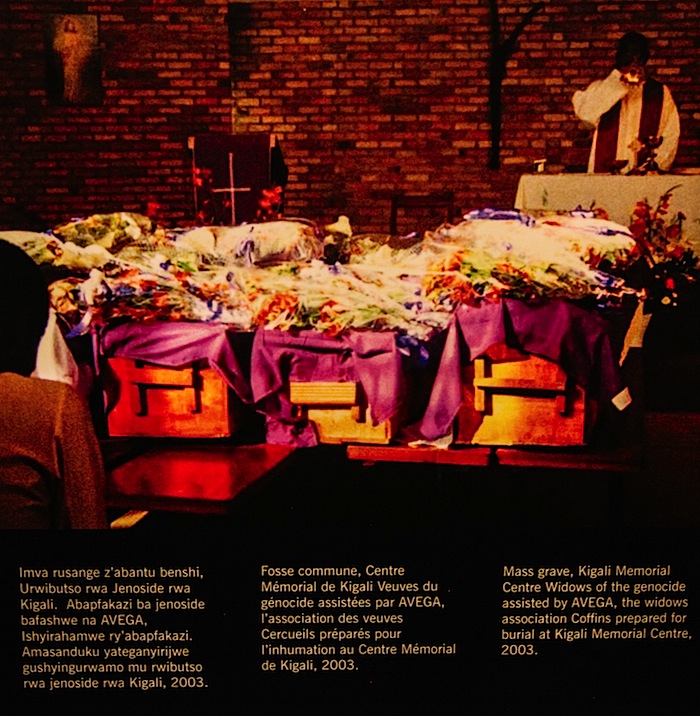

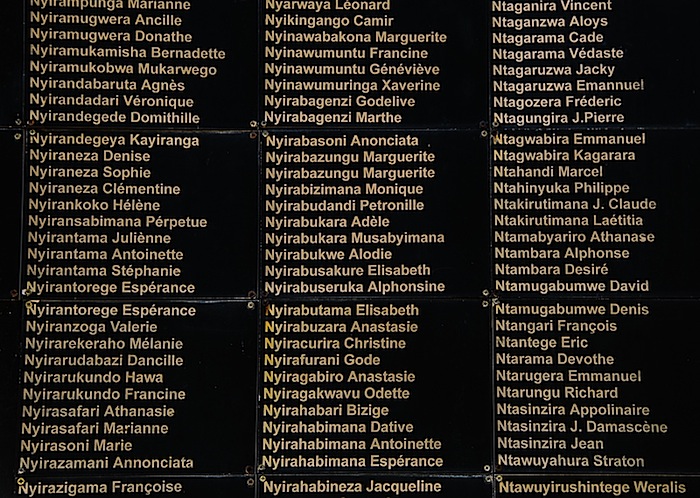

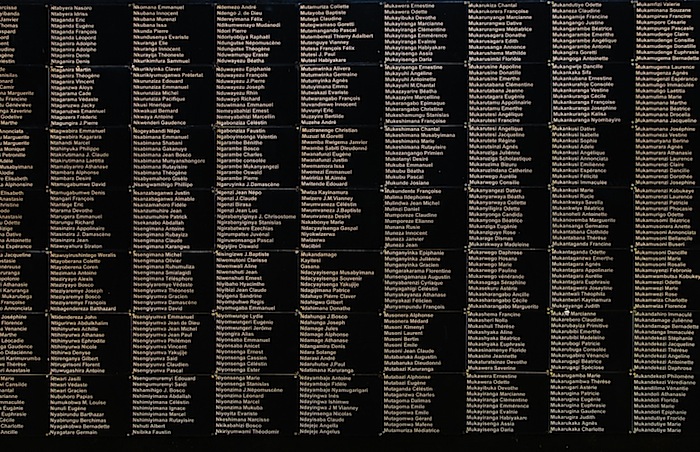

About a quarter of a million victims are buried at the Genocide Centre. Their names are listed on a very, very long wall.

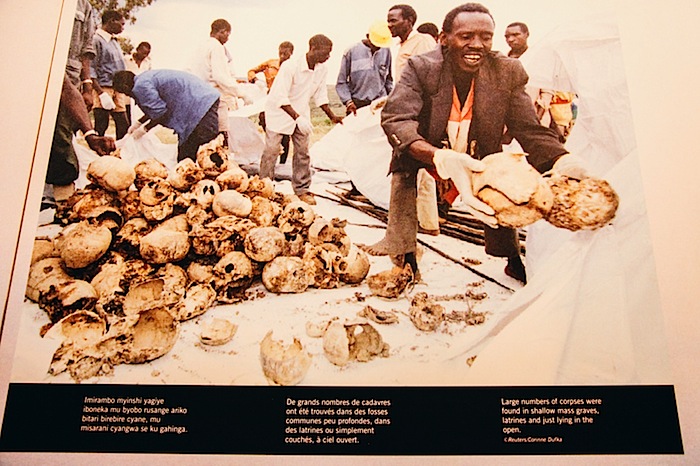

1994 was a dark chapter in Rwanda’s history and the fallout echoes loudly in their society today. For people my age — 30 years old — their childhood was informed by the murder of their relatives and friends. A woman interviewed in museum video footage explains that during the genocide, Rwanda felt like another planet — people were murdered minute after minute, the streets were littered with bodies… she saw a baby trying to breastfeed on its mother’s dead body. She describes the whole three months as an out-of-body experience; it didn’t feel like real life. How could bearing witness to such oppression NOT inform your emotional development as a human being? For those lucky to have escaped death, their lives have been scarred by heinous tragedy.

Hi there,

I’m just wondering if these photos were taken with permission of the memorial centre? When I visited 2.5 years ago they were very strict on their “no photo” policy, as it was explained to us that it was disrespectful to photograph inside of any memorial site. As meaningful as the photos are, I just wanted to make sure they were posted with approval.

Thanks

For $20 USD, guests at the Kigali Genocide Memorial may take photos and video inside the memorial. When I visited in July 2014 I believe it was $10 USD. You are not allowed to take photos if you do NOT pay that fee at the ticket counter upon arrival. For more information, please see here.